The unknown story of Te Whiti, a Māori chief from Hauraki, New Zealand

Posted on by Alice Bush.

by Polly Bence, PhD student at the universities of Bristol and Exeter. Polly is researching material culture collected from Australia and the Pacific Islands in Bristol Museum & Art Gallery.

Sensitivity warning: Some of the details in the blog reflect the attitudes of the British Empire and therefore include racist themes and terminology. I formally acknowledge the Māori community of Ngāti Maru and the Hauraki region of the North Island, New Zealand, and the descendants of the two men described.

Hand-coloured lithographic print of ‘Feedee’ (E1111)

‘Feedee’

Earlier this year I undertook a placement at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery. During my second week I came across this print. It is a representation of a Māori chief known in England as ‘Feedee’ or ‘Phede’, who was around 43 years old when he arrived.

He wears a kaitaka (woven cloak with a dyed taniko border) made of natural harakeke (New Zealand flax). Around his neck is a hei tiki (a highly-prized ornament) made of pounamu (nephrite). He wears a topknot secured with three white feathers. The portrait shows his chiefly moko (facial tattoos).

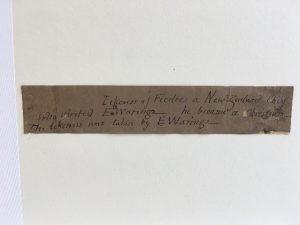

A label on the back of the frame reads: ‘Likeness of Feedee a New Zealand Chief who visited E. Waring – he became a Christian. The likeness was taken by E. Waring’. The print was donated by A.E. Ball, Berkeley Place, Clifton, Bristol in 1910.

Label from the ‘Feedee’ (Te Whiti) portrait.

Historians in New Zealand believe that the man is likely to be chief Te Whiti of the Ngāti Maru iwi (tribe) who travelled to England in 1827. He arrived with his nephew ‘Adic Hator’ (translated to Te Kato or Te Hato), who was around 23 years of age.

One of Te Whiti’s brothers (the village chief) had died fighting Hongi Hika, the much-feared chief of the North Island. Te Whiti and his nephew managed to escape on a ship bound for Sydney – but the vessel ended up in South America. Whilst working their passage on a ship to London, they met trader and conman Mr J. Johnson on board, whose real name was Joseph Riles.

He promised to return them home but suggested that they should first come to England and showcase some of their customs – for which he would pay them ten shillings a week. From London their first stop was Bristol, and Riles ‘exhibited them, contrary to their inclination’ (Derby Mercury, 12 May 1830). In Bristol, the two men were exhibited at the St James Fair.

St James’s Fair, Bristol by Samuel Colman (1824) © Bristol Culture

‘A tour’

For over three years the men were escorted and exhibited through several parts of the South West, Wales and the Midlands in a bid to raise money to secure their passage home. In Swansea and Neath they were invited to the homes of several principal gentlemen (Royal Cornwall Gazette, 17 November 1827), where they most likely met and sat for Elijah Waring (author, artist, reformer and Quaker, turned Wesleyan preacher).

It is impossible to truly understand Te Whiti’s experiences in England. The men were forced into this arrangement as they had become stranded with no hope of returning home by themselves. This type of coercion against ones free will is a form of slavery known as blackbirding. For as long as westerners had visited the Pacific region, Islanders have been intimidated, tricked, kidnapped and forced into agricultural work or performance for little or no reward, either against their will or without full knowledge of the life that awaited them.

Illness

Portrait of Hannah More, British School, Bristol Museum & Art Gallery (K3090)

In November 1829 the men had reached Derby where they both contracted measles. As this illness was unknown to Māori, they were badly affected. The man profiting from them had plans to take them to Ireland and the USA but on news of their worsening condition, abandoned them and left with their earnings.

The people of Derby and surrounding neighbourhoods raised enough funds for their return voyage. Donations to the cause included £4 from poet and abolitionist campaigner Hannah More of Clifton, Bristol. A Mr Waring of Neath, Wales also donated £5. The same Mr Waring who likely made the portraits.

In the spring of 1830 the Methodist missionary Reverend William Woon agreed to escort them to Sydney and arrange their passage back to New Zealand. Sadly Te Whiti’s nephew did not make it home, dying on board the ship.

Te Whiti did make it back to Hokianga on the west coast of the North Island in New Zealand on 17 January 1831. Sadly by February he also died at the missionary settlement at Paihia on the east coast, of inflammation of the kidneys.

Unfortunately this narrative is not unusual – countless people brought to Britain from the Pacific region never returned home.

Colonial collections

So why do we not already know Te Whiti’s story? Whose memories are we prioritising in our museums?

We need to give a platform to these important regional collections and archives. We have a responsibility to utilise these collections, learn their many narratives and redress inequalities in our museums.

__

This research has been possible due to a four-month placement funded by the South, West & Wales Doctoral Training Partnership. With thanks to curator, Lisa Graves and conservator, Eleanor Hasler at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, and to the historian, Vincent O’Malley in New Zealand.