The story of a stinky city: How improved sanitation transformed Bristol

Posted on by Fay Curtis.

by Lee Hutchinson, curator of history

When it came to the removal of human waste, for centuries Bristolians relied on the natural ebb and flow of tidal rivers.

During medieval times, underground water channels were built to drain sewage and rainwater from the streets. But this primitive system was not sustainable.

Bristol’s population increased from 20,000 in 1700 to over 300,000 in 1900. The population boom put a strain on the city’s infrastructure. By the 1800s, it was suffering with problems of overcrowding and high levels of sewage contamination.

The construction of the Floating Harbour from 1804-1809 effectively removed the tide from the harbour. While this improved the efficiency of the port, it compounded the problems of sewage disposal. The arrangement of dams and locks prevented the flow of the River Frome. Waste stayed put and the river became an open sewer.

When Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, visited the city in 1817, her carriage came to a halt at the drawbridge over the Frome. The bridge was entangled in a ship’s rigging. There was an awkward, drawn-out delay. This was embarrassing for the city officials – not only because of the setback, but because her Majesty was forced to endure a vile, lingering stench.

The hot summer of 1825 brought matters to a head. The accumulation of rotting sewage in the Frome and the Floating Harbour (the “Float”) was insufferable. There was a public outcry.

The Bristol Mercury described the scene:

“the effluvia from the sewage and the putrid carcases that floated on the surface of the water, presenting at the same time one of the most disgusting spectacles we can imagine, so strongly impregnated the atmosphere during the very hot weather as to make the neighbourhood of the Float intolerable to endure: the act of respiration, while passing the Drawbridge, was at once difficult and painful.”

The Dock Company was held responsible for running the port and maintaining the cleanliness of the water. It was seen to have failed in its duties. The Commissioners for Paving, Cleansing and Lighting took the company to court.

During proceedings, the Attorney-General highlighted the threat to public health: “If any person who falls into the river is not taken out within seven minutes, he is sure to be dead.”

The Mercury reported on an incident that had taken place only days before the sitting:

“On Tuesday evening, as a porter, belonging to the salt warehouse on the Back, was going on board a vessel for his coat, his foot slipped, and he fell into the water. The cries of his wife, who was a spectator, brought several persons to the spot; but, although he had been in the water only ten minutes, he was a corpse.”

The Dock Company was coerced into action. It commissioned William Shadwell Mylne to come up with a plan to dispose of the sewage.

Mylne’s proposal was to construct a culvert – a water tunnel – to carry the polluted water of the Frome underground to the New Cut. This would restore tidal conditions to the river and divert it away from the Floating Harbour. His plan was accepted. But it did little to solve the overall problem.

Only the highest tides could sufficiently flush the sewage from the banks of the Frome. The stench from the New Cut affected residents south of the city. And human waste still contaminated the harbour.

During the 1840s, an engineer – James Green – estimated that 20,000 tons of “solid matter” was entering the harbour each year.

Yet the Town Council was both reluctant and slow to act. Worse still, it was spending public funds on what the public considered unnecessary. The frustration of many turned to anger.

The Mercury suggested that councillors lacked any interest in the issue. They lived, it said, in houses on “breezy heights” in areas unaffected by poor sanitation.

“Their stomachs are not turned – their wives and children not made ill by the Froom and Float perfumes; nor are they obliged to close their windows in the hot days of June in order to exclude, as best they may, sickly and suffocating smells. That is the reason things continue as they are.”

Often, during stormy weather or high tides, sewage would wash back into people’s homes. An outraged member of the public, A. Burgess, declared that the Frome was choked with an “accumulation of filth” and “driving back the sewage into the houses of many thousand inhabitants… not only destroying their health, but injuring vast property.”

Dr William Budd was a physician to the Bristol Royal Infirmary. He gave evidence to the Health of Towns Commission, commenting that:

“… along the whole course of the stream is a source of noisome effluvia… Privies up and down the stream belonging to the houses which abut upon it hang over a bank of mud the level of which is only swept at spring tide… The state of things in the interval is too loathsome and disgusting to describe.”

The threats to public health were not only confined to the centre. A parliamentary report on the sanitary condition of Bristol was produced in 1845. It found overcrowding, poor sanitation, low standards of cleanliness, insufficient drainage and contaminated water in Lewin’s Mead, Temple and St Philip’s. Certain areas, like Bedminster, lacked drainage altogether.

Budd recognised that the key to preventing the spread of diseases such as cholera and typhoid was to improve sanitary conditions. This applied not only to the disposal of human waste but also to the provision of drinking water.

The privately owned Bristol Water Works Company, of which Budd was a director, was established in 1846. It began to supply a limited number of Bristol homes with fresh water from the Mendips. This was significant. Until then, only a few hundred families in Clifton had enjoyed the luxury of piped water from private springs. Most of the city’s inhabitants collected water from local standpipes. Well water could be delivered, but many of the poor could not afford the carriers’ charges.

In the spring of 1846, the council instructed James Green to tackle the sewage problem between Stone Bridge and Castle Moat. Green set to work, damming the Frome at Baptist Mills. This allowed the lower part of the river to be flushed with the waters of the Avon drawn from the Floating Harbour. These, in turn, ran via Mylne’s Culvert into the New Cut. When work was completed in the summer of the following year, the area was cleared of accumulated sludge. But it was still not enough to avert the threats to public health.

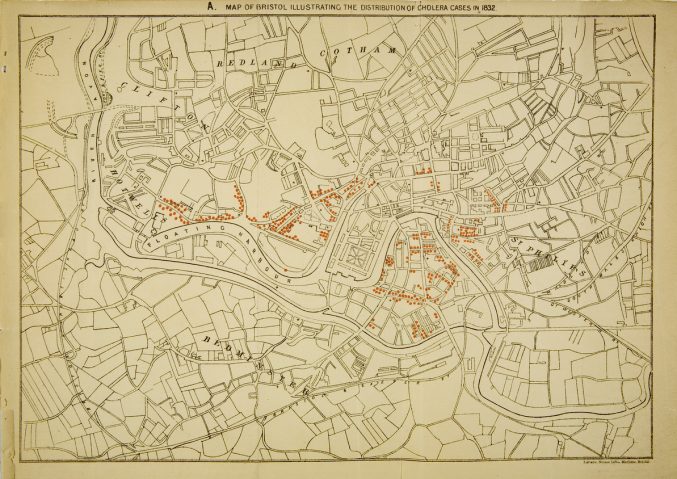

Poor sanitation culminated in devastating outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. Epidemics from the 1840s to the 1860s resulted in thousands of deaths. In 1850, a report on the city’s sanitary health noted that “Bristol was worse supplied with water than any great city of England.” Bristol was one of the unhealthiest cities in the country. In 1845 only Manchester and Liverpool had higher mortality rates. And, as with so many public-heath crises, it was the poor who were hardest hit.

The council feared further epidemics and further bad press. In 1851, spurred on by The Public Health Act of 1848, it established itself as a Local Board of Health. It set up a Sanitary Committee. Under the supervision of Frederick Ashmead, a surveyor (or civil engineer) the committee joined forces with the Bristol Water Works Company. A plan was put in place to install an impressive system of main drainage.

Measures were taken to reduce the number of cesspools, dung heaps, pigsties and slaughterhouses. The use of WCs was increased. Householders were compelled to make drain connections to the main sewers. Streets were paved to assist drainage. Slums were demolished. New, improved housing was built and overcrowding reduced.

In 1865, the City appointed its first Medical Officer of Health, Dr David Davies. He accepted Budd’s ideas about disease transmission and implemented a citywide disinfection programme. He was assisted by ‘The Sanitary Mission’, a group of women who provided practical help with cleaning and health care. By the following year, almost every house in Bristol had its own water supply.

Despite ongoing problems with overcrowding, infant mortality, and diseases like tuberculosis, measles, scarlet fever and whooping cough, the city’s health record significantly improved – a fact not lost on The Times. In 1869 it reported that Bristol was “nearly the most healthy town in Great Britain.”

![The Sanitary State of Bristol newspaper excerpt [From The Bristol Times, 1869]](https://www.bristolmuseums.org.uk/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/sanitary_state_of_bristol_times_1869-DETAIL-1-677x227.png)

In the language of individualism so characteristic of the age, it singled out three men for particular praise:

“Mr. Ashmead, the engineer, has carried out his plans of sewerage against much opposition, and their wisdom has been fully proved by their success. Dr. Budd has given time and thought without stint to the assertion and demonstration of what he holds to be the sound principles of disinfection, and the methods by which an enormous saving of life may be accomplished. In the practical application of these principles and methods Mr. Davies has triumphed over nearly every obstacle… He has hunted down disease with the keenness and perseverance of a bloodhound and with the ardour and sagacity of a sportsman”

By 1874, 43 miles of sewers carried sewage to the tidal Avon below the Cumberland Basin. The combined efforts to improve public health led to a marked reduction in the mortality rate – from 28 per thousand in 1852 to 18 per thousand in 1884.

The living environment of the city had been dramatically transformed.

Images

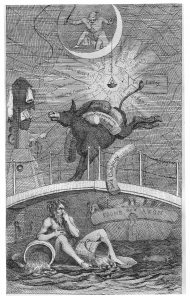

- ‘The Corruption of the Froom’. The Man in the Moon (a radical pamphletist) illuminates a web of corruption holding official documents. A kicking ass frees a bundle marked ‘Dock Company’. The deity of the Frome holds his nose at the stench. Two slop buckets empty into the river. Dead cats float by and a sailor vomits in the background. © Bristol Central Reference Library.

- Map of Bristol illustrating the distribution of cholera cases in 1832, from ‘Asiatic Cholera in Bristol in 1866’ by Dr William Budd, Bristol, 1871; ref. B656.Pb. © Bristol Central Reference Library.

- The Sanitary State of Bristol newspaper excerpt [From The Times, October 18, 1869]

Further reading

- Aughton, Peter (2000) Bristol: A People’s History; Carnegie Publishing, Lancaster

- Beeston, Anthony (2009) Bristol in 1807: Impressions of the City at the Time of Abolition; Redcliff Press, Bristol

- Bettey, J. H. (1986) Bristol Observed: Visitors’ Impressions of the City from Domesday to the Blitz; Redcliffe Press; Bristol

- Bush, Graham W. A. (1976) Bristol and Its Municipal Government, 1820-1851; Bristol Record Society, Gateshead

- Eveleigh, David J. (1996) Britain in old Photographs: Bristol 1850-1919; Sutton Publishing, Stroud

- Hardiman, Sue (2005) The 1832 Cholera Epidemic and Its Impact on the City of Bristol; Bristol Branch of the Historical Association, Bristol

- Jones, Donald (2000) Bristol Past; Phillimore and Co., Chichester

- Large, David (1985) ‘Proceedings of the Bristol Local Board of Health’, in McGrath, Patrick (ed) A Bristol Miscellany; Bristol Record Society, Bristol

- Large, David (1999) Bristol and Its Municipal Government, 1851-1901; Bristol Record Society, Bristol

- Large, David and Round, Frances (1974) Public Health in Mid-Victorian Bristol; Bristol Branch of the Historical Association, Bristol

- Malpass, Peter and King, Andy (2009) Bristol’s Floating Harbour: The First 200 Years; Redcliffe Press, Bristol

- A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers, Vol. 1. 1500-1830. (2002) Ed. Sir Alec W. Skempton et al; Thomas Telford Publishing, London

- Bristol Historic Population Statistics (Bristol City Council)

- ‘Law Proceedings Relative to Bristol: Court of King’s Bench, Wednesday, Feb. 8. Motion for a Mandamus’ in The Bristol Mercury, Monday, February 13, 1826; Issue 1830.

Newspaper articles

- ‘The Floating Harbour’ – The Bristol Mercury, Monday, July 10, 1826

- ‘Letter to the Editor’ – The Bristol Mercury, Tuesday, May 27, 1828

- ‘Letter to the Editor – The Town Council’ – The Bristol Mercury, Saturday, October 26, 1839

- ‘Health of Towns – City Nuisances and their Consequences’ (Third Article) – The Bristol Mercury, Saturday, May 30, 1846

- ‘Letter to the Editor’ – The Bristol Mercury, Saturday, June 20, 1846

- ‘The River Froom’ – The Bristol Mercury, Saturday, July 17, 1847

- ‘The Sanitary State of Bristol’ – The Times, October 18, 1869

3 comments on “The story of a stinky city: How improved sanitation transformed Bristol”

In around 1964/65 I, as a representative of IBM the computer manufacturer, and having trained as a civil engineer, had contacts with Bristol Waterworks, who used an IBM computer. A very enterprising engineer there wrote computer programs to analyse their water systems in Fortran ( the then popular scientific programming language) – including basing some on traffic analysis programs, as a traffic system has similar ‘ins and outs’ ! The ‘Centre’ in Bristol was amongst his analyses, and he claimed he significantly added to their knowledge of the area.

I must take issue with the suggestion that David Davies was a progressive. It is true that in relation to infectious diseases he aligned himself with people like Dr Budd but on the vexed question of insanitary housing he was the exact opposite of progressive. His strategy was to deny that there was a problem of, say, overcrowding, then he would deny that he had any powers to deal with it and then deny that any action taken would have a beneficial effect. He set all this out in evidence to the Royal Commission of housing in 1884, and was roundly criticised by one of the commissioners for his evasiveness and ignorance of the legal powers at his disposal. Davies was sneeringly dismissive of the Poor Law guardians who called on him to take action on some grossly insanitary courts near Lewin’s Mead in 1877. And he freely admitted that rather than do anything about slum courts and alleys he relied on the council’s streets improvement committee to deal with the problem. I could go on, for instance to point out how Davies was inclined to blame infant mortality on the habits of parents, including the fact that women were going out to work. No, he was no progressive.

Thank you for your detailed and informative feedback, Peter. The article has now been amended to retract the suggestion that David Davies was a progressive.