Decorated wall fragments from the funerary temple of Mentuhotep II in Bristol Museum & Art Gallery

Posted on by Fay Curtis.

by Maarten Praet, Ph.D. Student – Egyptian Art and Archaeology at the Johns Hopkins University

I am studying the reign of the ancient Egyptian king Mentuhotep II (2055-2000 BCE) for my PhD dissertation at the Johns Hopkins University. Specifically, I study the fragmentary decoration from Mentuhotep’s funerary temple. This temple is located in the Deir el-Bahari valley on the west bank of the river Nile. Mentuhotep is important in ancient Egyptian history. He reunited Egypt under his sole rule after a period of political fragmentation. He also made important artistic, political, societal, and religious innovations. These innovations lasted for more than 2000 years.

- Fig. 1: List of objects from the temple assigned to Bristol Museum & Art Gallery

- Fig. 2: List of objects from the temple assigned to Bristol Museum & Art Gallery

In 1903-1907, the Swiss Egyptologist Édouard Naville found about 3000 decorated wall fragments of the temple. During his excavations, he took around 1000 out of 3000 fragments out of Egypt. This happened under a system called partage.

The system was negotiated in 1883 with the French colonial powers in charge of the Antiquities Service. It allowed excavators to choose some of the objects they found. They could then take them back to their home countries. At that time, most excavations were funded by wealthy private donors or museums and universities. For example, Lord Carnarvon sponsored Howard Carter’s excavations. This led to the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb.

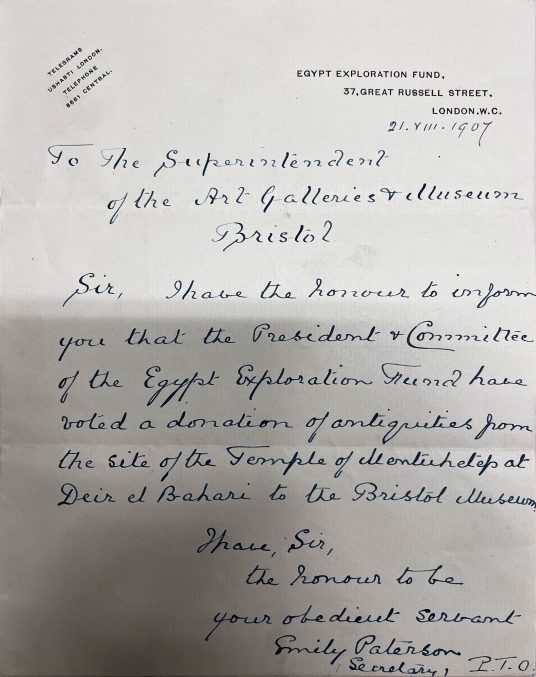

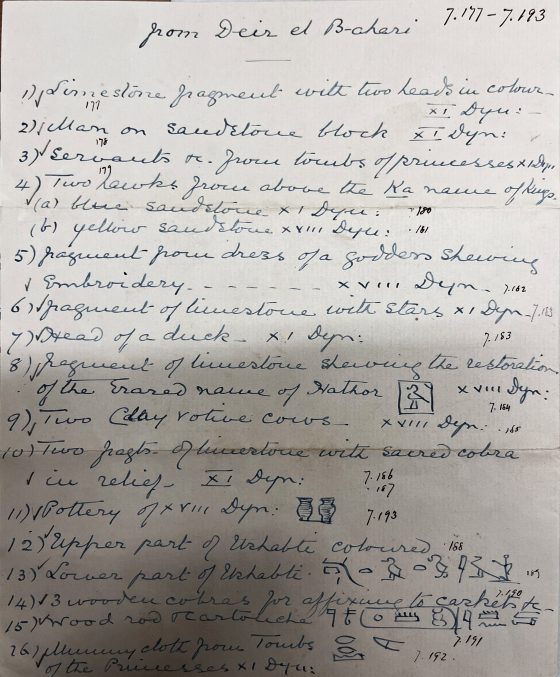

The partage system also contributed to creating current collections of ancient Egyptian artifacts outside of Egypt. For instance, Bristol Museum & Art Gallery received 17 fragments taken out of Egypt by the agents of the Egypt Exploration Fund. 1 & 2). Some documents in the archives of the Museum and the Egypt Exploration Society in London show the relations between both institutions at the beginning of the 20th century. They also provide more details about the process of dividing the excavated objects after they had reached London. (See the list of objects assigned to Bristol in fig. 1).

Other archival documents, such as the excavation journals and the photographs taken during and shortly after the excavation, also aid in piecing together the modern history of these objects. They might shed light on where exactly in the temple certain objects were found. They could also reveal when the objects were first transported to London.

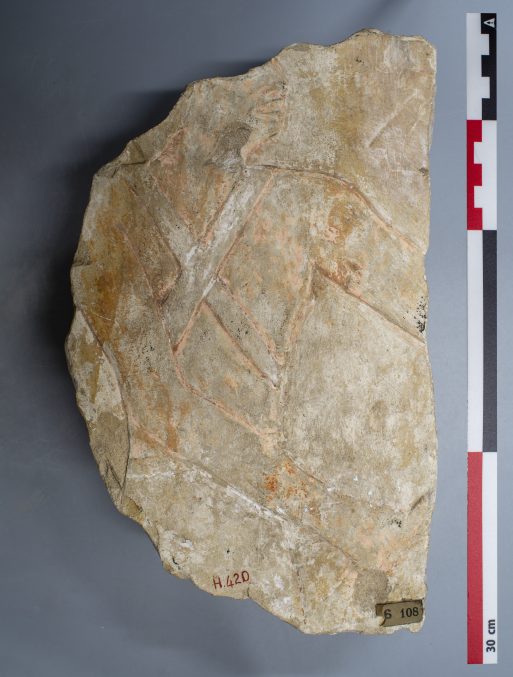

- Fig. 3: H420 – Photographer: Maarten Praet

- Fig. 4: H419 – Photographer: Maarten Praet

In June of 2023, I conducted a month of research in London, very kindly supported by the Robert Anderson Trust. I studied the decorated wall fragments from the temple of Mentuhotep II in the British Museum, the Petrie Museum, and Bristol Museums.

In Bristol Museums, I measured, photographed, and studied all 17 blocks. Their content ranges from depictions of human figures, such as soldiers (fig. 3) and herders, to parts of the name of king Mentuhotep, and a gorgeous depiction of a hippopotamus (fig. 4). These fragments all belonged to larger scenes decorating the walls of the temple.

Each scene might contain information about Mentuhotep’s religious and political policies. Kings usually used wall decoration in ancient Egyptian temples for propaganda. That’s why I’m trying to reconstruct the scenes as best as I can using the available fragments. For instance, fragment H419 in Bristol Museum & Art Gallery shows a hippopotamus in water. This fragment must have come from the same scene as two other fragments. These fragments are now preserved in the British Museum (fig. 5) and the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum (fig. 6). One shows another hippo, whereas the other shows a crocodile eating a fish.

The archival pictures from the Egypt Exploration Society’s archives show similarities between these fragments and the fragment in Bristol. Yet, what larger scene could these three fragments have belonged to? Better preserved examples of wall decoration from earlier royal funerary temples are useful in the reconstruction process. They provide examples of what different scenes could have looked like in the temple of Mentuhotep.

- Fig. 5: DB_05_06_0153 Courtesy of Egypt Exploration Society

- Fig. 6: DB_05_06_0167 Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society

More and more virtual projects are currently launched to make ancient Egyptian objects and monuments accessible. After I finish my PhD, I plan to virtually reunite all decorated wall fragments from the temple of Mentuhotep II. I also aim to make this monument accessible to audiences in Egypt and the rest of the world. Explanations about Mentuhotep and his temple in Arabic and English are thus vital.

One comment on Decorated wall fragments from the funerary temple of Mentuhotep II in Bristol Museum & Art Gallery

This is fascinating – looking forward to seeing the pieces virtually reunited. I’m currently studying Egyptology (virtually) through Manchester University and have just reached Mentuhotep on the course. I also live in Bristol so going to see these pieces again with the context you’ve added will be great.