Decolonising the Bristol Archives catalogue

Posted on by Alice Bush.

By Sophie Welsh, third-year PhD student at the universities of Exeter and Southampton

Hello, my name is Sophie Welsh. I’m a third-year PhD student at the University of Exeter and the University of Southampton. I took a short break from my PhD to work on a six-month placement with Bristol Archives to make records related to enslaved people more identifiable in the online catalogue. In this blog I’ll share the goals of the project and some of the discoveries I made.

Bristol’s historic involvement and interest in profiting from enslavement is well recorded in the city archives. Letters, financial agreements, records of plantations and many other documents show how people in Bristol invested in and profited from the trafficking and enforced labour of African people.

Ashton Court, home of the Smyth family, who enslaved African people on their plantations in Jamaica (ref. 43207/9/13/081)

While these records are available to anyone who wants to consult them, many are difficult to locate in catalogues that do not fully document this context. The existing catalogues were written over a period of several decades and Bristol Archives staff recognised that many entries needed to be improved.

This project aims to ensure that the catalogue more clearly identifies people and activities related to enslavement. The goal is to make researching Bristol’s history of involvement in the economy more accessible. To do this, I have updated and enhanced catalogue descriptions. Researchers can then more easily identify this material, as well as being suitably prepared to encounter it when they consult documents in the searchroom.

Language has an important role to play in the ways we think about the past. Coming from a PhD in English Literature, I paid attention to the language used to describe materials related to the trafficking and labour of enslaved people. I also used my research skills to shed more light on the contents of the archives. I did this by adding in historic context and identifying previously unacknowledged material.

This is not a project to re-write Bristol’s history. It is about illuminating that history fairly and accurately, without reproducing the ideas of the past. I aimed to be as objective as it is possible to be when dealing with material of this nature and we’ve kept a record of all the changes made.

I began by focusing on the largest collections with clear ties to transatlantic slavery. These include the records of the Smyth and Woolnough families of Ashton Court, the Southwell family, the Bright family and the Society of Merchant Venturers (SMV). Starting in this way means I was able to identify the kinds of records and the recurring names related to enslavement.

Edward Southwell Jr (1705-1755) was an MP who owned Kings Weston House. His business papers document Bristol’s role in trafficking and enslavement (ref. PicBox/6/Port/KW/7).

Many figures involved in the slave economy appear across various collections, such as Thomas Daniel, Sir James Laroche, Philip Protheroe and Thomas Farr, who invested in slaving voyages or owned plantations and were members of the SMV. However, they are not all represented by large collections in the archive. Working with the archives staff, I created an index of names that makes it easier to discover information about key players. For example, Farr does not have a family collection in the archives – unlike, say, the Bright family (ref. 11168). However, he appears across more than five different collections that reveal he was a significant figure in the trade, being a master of Merchants Hall, a sugar merchant, an investor in slaving voyages and an anti-abolitionist. He was also mayor of Bristol and an early owner of the Blaise Castle Estate.

Listing key figures and organising them alphabetically also helped to identify family names associated with the trade that might otherwise have been unnoticed. For example, six separate members of the Champion family appear in collections related to the SMV. Richard Champion, a merchant and porcelain manufacturer, is represented by a collection in the catalogue (ref. 38083) but the catalogue did not note that he settled in South Carolina as a ‘gentleman farmer’ of a slave plantation (see Bristol Record Society’s Publication Vol. 55, The Diary of Sarah Fox née Champion). Further work could also be done to explore his family’s possible connections to transatlantic slavery through the SMV.

I consulted original documents to pick out details to expand their descriptions. For example, the catalogue often used the blanket term ‘Africa’. I changed this to specific place names such as the St Andrews River in Gambia, Callebar in present-day Nigeria and Annamaboe in present-day Ghana (refs. SMV/7/2/1/7, 45039). Adding both historic and current place-names provides much more detail on how and where Bristol merchants traded people as assets on the continent.

I also revised catalogues to ensure records are sensitively described. An entry about the records of Spring Plantation, Jamaica, owned by the Woolnoughs, described the ‘evils of hurricanes’ on plantations, and side-lined the actual evils of enslavement. I tried to prioritise the people who were suffering under these conditions. One method is to make a simple change from ‘slave’ to ‘enslaved person’. This use of language challenges the idea of slavery as intrinsic to a person’s being. Instead, it highlights that people were subjected to the conditions and abuse of enslavement.

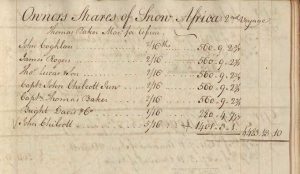

An extract from the accounts of the Snow Africa, a ship which transport enslaved people from African ports to the West Indies (ref. 45039)

Historically, people of colour are largely invisible in British archival records related to enslavement, except as property or assets. To help remedy this, I pulled out details from various documents, where available. For example, a report on a slaving voyage at Annamaboe (present-day Ghana) (ref. SMV/7/2/1/7) describes enslaved people dancing on the deck of the ship Greenwich. Noting this in the catalogue shifts the perception of people as passive products. Instead it draws attention to them as people with agency who were enslaved.

By failing to recognise the racist aspects of a city’s history, we can also forget the history of anti-racism that went alongside it. For example, filed among a series of pro-slavery pamphlets is a report from the ‘Bristol and Clifton Female Anti-Slavery Society’ from 1829 (ref. SMV/8/3/4/2). Other records show that attendees of an anti-abolition meeting in 1789 had also attended the city’s first abolition meeting in 1788 (ref. SMV/8/3/2). This kind of detail cuts against the narrative that slavery was a universally endorsed practice in the past. In fact, it was resisted even in a city that had profited from its existence.

The updated catalogues went online this summer. However, the Bristol Archives collections related to enslavement would take years to study in full, so I’ve created a list of recommended future archival work on the rest of the collections. I look forward to seeing this work carry on at Bristol Archives and hopefully in other archives around the UK too.