Tales from the Ark-hive: Six fascinating stories from the natural history stores

Working with curator Rhian Rowson, Bristol University researcher Rachel Murray spent time in the natural history store at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery. Here she uncovers some of the stories behind the collection…

The natural history store has 700,000 specimens of mammals, birds, insects, and plants. In many ways it resembles the ark built by Noah to save two kinds of every animal from the Flood. If it exists in nature, you’ll probably find it here, stowed safely in the depths of the Museum. As well as containing the first documented examples of new species (known as ‘type specimens’), the collection also houses a number of extinct creatures. The passenger pigeon, the Irish elk and the thylacine have been carefully preserved.

The heyday of specimen collecting has been and gone, but the store remains a hive of human activity. Scientists, artists, photographers, filmmakers, students and school children all use it. The collection is constantly studied, researched, documented, and illustrated. Some specialists gather vital information, contributing to pressing issues such as climate change. Others record the diversity, colour, and complexity of the animal kingdom for art or education.

There is another definition of the natural history store: it’s an archive of historical documents collected over the past 150 years. It forms a record of Bristol’s engagement with the natural world from the Georgian era to the present day. The store is a rich repository of life frozen in time, and each preserved specimen has a story to tell. Many of these tales are yet to be told. Below is a small selection of objects that offer an insight into the store’s cultural, historical, and scientific value.

Whale have you baleen?

While searching in the store, curator Rhian Rowson rediscovered a section of baleen (a filter-feeder system inside the mouths of baleen whales) from the famous Littleton Pill whale. It had lain unnoticed in the collection for decades.

The baleen belonged to a 66-foot common fin whale. The whale became stranded in the Severn estuary at Littleton Pill, Gloucestershire in early January 1885. It was discovered early one morning by local resident Isobel Durnell, who initially mistook the giant object for a house washed up by the tide.

The whale quickly became a major tourist attraction. Local newspaper reports described the tens of thousands of visitors who flocked to see it during the two weeks it lay beached at Littleton. The Midland Railway Company even ran a special train service to take Bristol residents to see it.

The Littleton Pill whale was then towed down the Avon to Bristol by steam tug. It was exhibited for a further fortnight, before being sold for £40. Although its skeleton was preserved, its whereabouts remains a mystery. All that remains in the store is this small section of plate from the roof of its mouth. The fine hairs that fringe it are a substitute for teeth, and were used as a sieve to catch krill, small fish, and copepods. The smooth grooves in its surface resemble those in our fingernails. Baleen is made of the same material – keratin – that forms them.

The poet Charles Tomlinson, who spent much of his life in Gloucestershire, pays tribute to the baleen in ‘The Littleton Whale’, a poem inspired by first-hand accounts by local residents:

And the crowds came

to where it lay

upside down

displaying a belly evenly-wrinkled

its eye lost to view

mouth skewed and opening into

an interior of tongue and giant sieves

that had once

filtered that diet of shrimp

its deep-sea sonar

had hunted out for it

by listening to submarine echoes

too slight

for electronic sensation…

Over time, the delicate hairs on the baleen have stiffened into bristles. But there is still something surprisingly supple about the structure as a whole. In the Victorian era, baleen was considered strong and flexible. It was used in the manufacturing of corsets, collar stiffeners, backscratchers, and parasol ribs. Today, we value the baleen as the surviving remnants of a vast cetacean stranded on the Severn estuary. Once lost to obscurity, but lately brought to light again.

The baleen has curved over time into the shape of both the creature and the waves that carried it. Although it may have dried out, it still gleams like the surface of the water and the whale in which it lived. Scientists have recently discovered that baleen contains a time-stamped map of the whale’s journeyings. This provides information about the oceans it lives in, where it feeds, and what it’s eaten along the way. In these grooves and hairs, there is a life story to be told – one that may answer the question: whale, where have you been?

Suspicious seagull

On 28 January 1915, while Britain was at war with Germany, a black-headed gull was seen acting suspiciously near Horfield Common. Several bystanders reported seeing the bird flying low and screaming as though in pain. It was then found dead on the Common with a ring on its leg that read ‘Lotos-Prag, Austria’.

Bristol resident James Barker alerted the Museum to this mysterious case. He wrote that ‘the spelling of the words ‘Lotos-Prag’, prove that the bird had been in German hands’, and enclosed the bird for further inspection. Barker added that it is ‘impossible to find out for what purpose this bird was set free from Prague bearing this ring’. The implication of the letter is clear: this gull may have been working for the enemy!

Barker’s suspicions were understandable. The presence of this Bohemian bird in Bristol, more than 800 miles from home, would’ve been unusual even in peacetime. During the First World War, pigeons were often used as messengers due to their speed, altitude, and homing ability. One pigeon, nicknamed ‘The Mocker’, flew 52 missions before being wounded. Another, known as ‘Cher Ami’, was awarded the French ‘Croix de Guerre with Palm’ for heroic service delivering important messages during the Battle of Verdun.

On her final mission in October 1918, ‘Cher Ami’ delivered a crucial message, saving the lives of 194 American soldiers. This was despite having been shot through her breast or wing.

During the First World War, the Prussian War Ministry experimented with pigeon photography for the purposes of aerial reconnaissance.

The Director of the Museum sent the gull off to top taxidermists Rowland Ward in London to be mounted. A note was prepared that explained the bird’s backstory. Was this gull spying for the Germans? To this day, it has guarded its intelligence carefully, but who knows what secrets might be stored beneath its feathers?

Image: German Federal Archives

Golding’s conch

In colour the shell was deep cream, touched here and there with fading pink. Between the point, worn away into a little hole, and the pink lips of the mouth, lay eighteen inches of shell with a slight spiral twist and covered with a delicate, embossed pattern.

Lord of the Flies

A few years ago, the Museum received a letter from William Golding’s daughter, Judy Golding Carver. In it, she revealed that the conch shell that features in his famous novel, Lord of the Flies, was inspired by the author’s trips to Bristol Museum as a child in the 1920s and 30s.

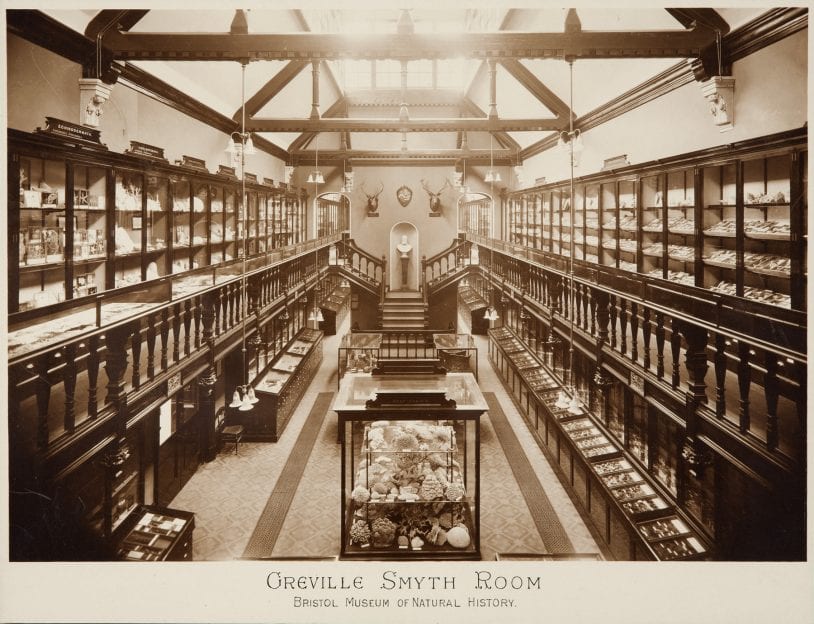

The conch featured in a display case in the Bristol Museum of Natural History, in the building that’s now Browns restaurant. This is where the natural history collection lived before the building was severely damaged by a Second World War bomb. It was then moved to the Art Gallery further down the road, where it remains today.

The Bristol Museum of Natural History

The Bristol Museum of Natural History A rhino standing in the bomb-damaged Bristol Museum of Natural History building

A rhino standing in the bomb-damaged Bristol Museum of Natural History building  Bomb damage to the Bristol Museum of Natural History

Bomb damage to the Bristol Museum of Natural History Golding’s grandfather, Joe Golding, was a Bristol boot-maker who lived in Kingswood. While visiting his grandparents Golding spent time in the museum. He made lists, annotations, and drawings of the various items on display. During one visit to Bristol, the young Golding even dreamt that he was one of the museum curators. It wasn’t until he visited the museum the next day that he realised that this couldn’t be the case!

During his time as an undergraduate at Cambridge University, Golding studied Natural Sciences before transferring to English Literature. The representation of the conch in the Lord of the Flies passage above combines scientific accuracy with literary symbolism.

Natural history curator Rhian Rowson believes that the conch described is this Charonia tritonis shell from the Museum collection. This shell is found throughout the Indo-Pacific oceans. Lord of the Flies is also set on an unnamed Pacific island, and the Charonia tritonis was used as a trumpet on South Pacific islands such as Fiji. It’s not possible to find out exactly which conch shell Golding would have seen on display. But it’s exciting to learn that the Museum provided the inspiration behind one of the most famous shells in literature!

Living fossils

We mostly think of dead specimens when we think of museums. But in 1911 the curators at Bristol Museum received a package from Wellington, New Zealand. It contained two live Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus). These prehistoric reptiles were a gift from Colonel F. G. B. Sanders, who had visited the Museum previously. Sanders had informed museum director Herbert Bolton that he would be happy to donate specimens of this rare creature. The only trouble was, the Tuatara that Sanders donated were not preserved specimens, but living lizards.

The Museum generally transferred live donations to Bristol Zoo Gardens. In this case they decided to keep the Tuatara, installing them in a display tank alongside cases of taxidermied specimens. This is consistent with their unusual status in the animal kingdom as ‘living fossils’. They are organisms that are otherwise known only through the fossil record, which have retained their features for hundreds of millennia.

The arrival of the Tuatara at Bristol Museum was also something of a homecoming. In early 2018, fossils collected during the 1950s in a quarry near Cardiff were discovered to belong to a new species of ancient reptile. The Clevosaurus cambrica is a relative of the New Zealand Tuatara. In the late-Triassic age, the hills of South Wales and the South West of England formed a group of islands where small dinosaurs and reptiles lived. Many of these were related to the two creatures living in the Museum.

Image: Tuatara in New Zealand by Sid Mosdell, CC BY 2.0, Link

One of the Tuatara died a few years after arriving in Bristol. The other lived in the museum for fourteen years, and appears to have thrived on the attention it received from visitors. Director Herbert Bolton noted that when faced with a group of children, ‘however sluggish it may have been before’, the tuatara would:

go over to the side of the case with the head held up and watch the children as long as they choose to stay there, making very few movements beyond a slight inclination of the head, first to one side and then the other. It would almost seem to be pleased by the attention it receives.

Bolton also warned that the creature ‘can be handled, but only with care, as it is capable of inflicting a very severe bite’.

The remaining Tuatara eventually died in 1925 following a short illness. Its death was not only announced in the Museum’s Annual Reports, but Herbert Bolton arranged for its skeleton to be mounted ‘in as life-like a position as possible’ for future visitors. Today, the Tuatara is stored in the safest part of the Museum alongside some of its most valuable treasures.

Mutant rats

Herbert Bolton, the Director of the Museum from 1898 to 1930, often received letters informing him of the discovery of a new species. Acquiring examples of new species for the collection was highly desirable. It meant that museums remained up-to-date with new scientific developments. Selling new specimens to museums could be a lucrative enterprise. Not all newly discovered species, however, were entirely legitimate.

In 1921, Bolton received a letter from H. C. Brooke of Taunton. Brooke’s letterhead said that he was the ‘First English Breeder of Wolf-Dingo Hybrids’ and the ‘First Exhibitor of Rattus Varieties’. Brooke informed Bolton that he had recently discovered a new breed of mutant rat that was native to the Bristol docks. Its creamy white fur and black eyes set it apart from existing rodent varieties. Scientists had agreed that it had never been seen before.

Brooke named this new variety after himself, and enclosed a clipping from a genetics journal entitled ‘A Mutant of the Old English Rat’. This confirmed that the Rattus rattus brookei had been recognised by members of the scientific community. Brooke also informed Bolton that the Natural History Museum in London had already bought one of the rats, and that another ten specimens had been sent to a professor of genetics at Harvard University. Brooke’s rat was in demand!

Bolton appears to have recognised the appeal of this Bristolian mutant to the local public, and agreed to purchase two specimens. However, when Brooke wrote to the Museum again two years later informing them that he had discovered another new variety of vermin, Bolton began to smell a rat. Brooke announced that he had discovered a further species of mutant rat ‘the colour of a blue Persian cat’, and would the Museum like to purchase a few of these blue specimens? Brooke hastens to add that he had been in touch with curators of museums around the world, who had confirmed that this species of rat was unknown to them. This time, however, the Museum politely declined the offer, and given that Brooke’s rats are no longer recognised as an official subspecies of rat, the decision was a sensible one.

It’s possible that Brooke really was convinced that these pale dock dwellers actually were a new species – the result of cross-breeding of various verminous visitors transported to Bristol from around the world. But given that Brooke’s rodents also bear a striking resemblance to the relatively common albino rat, these mutant Muroidea may also have been little more than furry frauds.

A Fenland visitor

The many-lined moth (Costaconvexa polygrammata) was first classified in 1794. It became extinct in Britain in the late-nineteenth century. It was known to live in the marshes of the Cambridge Fens in eastern England and damp meadows near Bristol. But until recently there were no known specimens collected from the Bristol area.

Scientist Peter Andrews was looking through a collection of lepidoptera (an order of insects that includes butterflies and moths) in the Museum store. He discovered a many-lined moth specimen labeled ‘Bristol’. After investigating further, Andrews concluded that the specimen was collected here in 1870. This confirms that a small population of many-lined moths inhabited the West Country as well as the Eastern Fens.

With a collection as rich and diverse as Bristol’s, it might seem surprising to focus on this unremarkable looking straw-coloured moth with its obscure wing pattern.

Moths are often considered the dull sibling of the more colourful butterfly family. They tend to be either overlooked or feared by humans. But moths pollinate flowers and ensure a good harvest of crops. They are also vital indicators of changes to local environments – the effects of pesticide use, the introduction of invasive species, as well as the consequences of air pollution and climate change.

Some of Britain’s moths are increasing in number. But in recent years many have gone into dramatic decline. A 2013 report reveals that three native moth species have disappeared in the past decade, and that overall moth numbers are down by 40%.

Image: Mazarine Blue, Polyommatus (Cyaniris) semiargus, by gailhampshire Malvern, U.K – CC BY 2.0

The many-lined moth discovery shows the ways in which the collection can help us to understand biodiversity, past and present – how it has changed over time, and how further species loss can be prevented in the future. A recent article in the science journal Nature stated that by examining historical specimens in a museum collection, researchers are much more likely to learn new things about an existing species or to discover new species . As opposed to heading out into the countryside with a pair of binoculars.

The natural history collection at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery makes disappearances visible. It provides a lasting record of what we’ve lost, and what we still might lose. In addition to the many-lined moth, the store contains preserved British specimens of the extinct mazarine blue and large copper butterfly. These serve as haunting reminders of the colour, beauty and diversity that have already been lost.

The news is not all bad. In the past few decades, rare immigrant many-lined moths from central Europe have been spotted on the southern coastline in Dorset.

Were the 19th Century sightings in East Anglia and Bristol due to transient populations being established? Or has the moth always been just a visiting migrant in some years? As further research is done into this former moth of the West Country, it may be possible to learn more about the conditions that will help the species to settle and thrive in Bristol.