The story behind the book is one of controversy and Dr Richard Smiths’s fascination for collecting macabre death memorabilia.

Dr Richard Smith Junior

Dr Richard Smith (1772-1843) was a surgeon at Bristol Infirmary from 1796 until his death.

Amongst other things, he is known for his anatomisation of executed criminals. In April 1802 he dissected the bodies of two women hanged on St Michael’s Hill for infanticide; he dissected and lectured upon the brain of another convicted criminal in front of the Mayor and Aldermen.

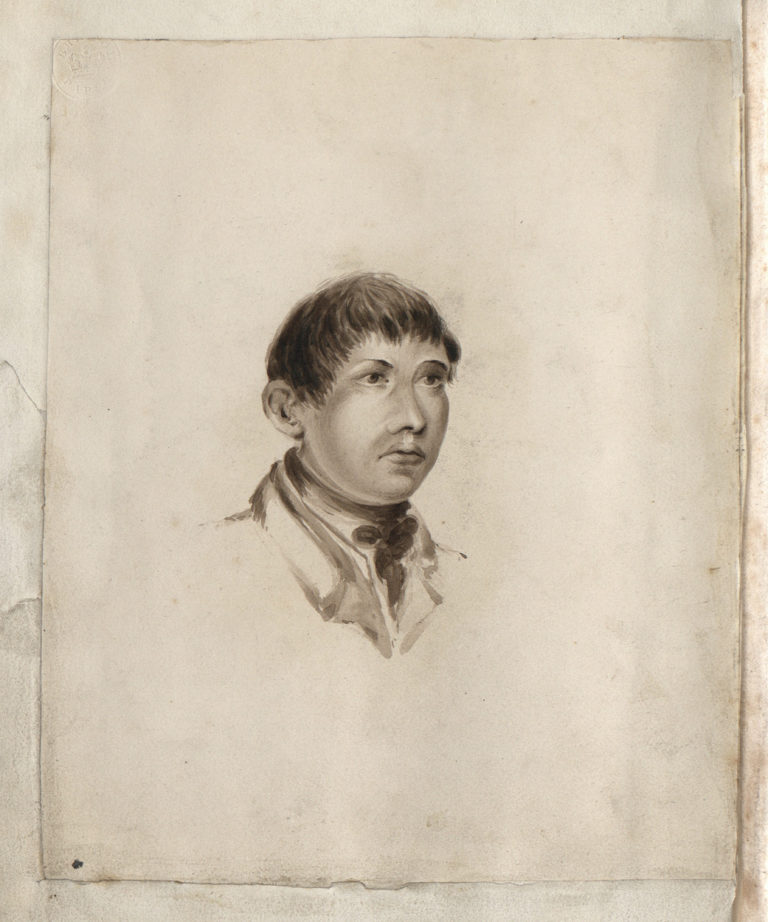

He cut up a body found in a lead coffin near St Mary-le-Port in 1814, removing the brain for his anatomical museum.

The body was believed to have been that of Robert Yeamans, one of the “royal martyrs” executed in 1643, despite the fact that he was supposed to have been buried in Christ Church.

Image: Mr Yeamans at his Disinterment, 1814 by John Samuel Miller

In 1828 he had a collection of papers bound in the tanned skin of John Horwood, who had been executed for the murder of Eliza Balsum.

The execution of John Horwood

“John Horwood, convicted of the wilful murder of Eliza Balsum, Let him be instantly hanged by the neck until he shall be dead on Friday the 13th April instant, and let his body be delivered to Richard Smith, of the City of Bristol, Surgeon, to be dissected and anatomised.”

Court order at the trial of John Horwood, 1821

On Friday 13 April 1821, Bristol’s New Gaol hosted its first public execution. John Horwood, aged 18, was hanged for the murder of Eliza Balsum, an older girl with whom he had become infatuated. When she had rejected his advances, he had thrown a stone at her, striking her on the head as she crossed a stream.

She died a month later after being operated on by surgeon Dr Richard Smith. Horwood’s body was given over to Smith at the Bristol Infirmary for his anatomy class. At that time anatomisation was a part of the punishment for murder.

He had Horwood’s skin preserved, tanned and then used it to bind a book.

The Horwood Book

The John Horwood book is one of the UK’s few surviving examples of a book bound in human skin. But why does a book bound in human skin exist?

To understand we must go back to the early 1800s. There was a growing belief among surgeons that knowledge of the human anatomy was essential to the practice of medicine, including surgeons at Bristol Infirmary.

For many years, there was a growing need for fresh corpses for dissection. This led to the illicit removal of corpses from graveyards or “body snatching”. Obtaining bodies for dissection was poorly regulated – there was a lot of money to be had in the lurid grave-robbing business, and cases increased.

During the mid-1700s Parliament had resolved to “add some further terror and peculiar mark of infamy” to death by hanging. It was decreed that executed criminals should have their bodies sent for dissection.

Miscellaneous papers etc. re the case of John Horwood executed for murder. Bound in human skin.

Read more

In 1828 Smith had a collection of papers bound in the tanned skin of John Horwood. The Latin inscription on its front cover reads ‘Cutis Vera Johannis Horwood’, which translates as ‘the actual skin of John Horwood’. Surgeon Richard Smith carried out the dissection of John Horwood for a group of students in the Operation Room at the Bristol Infirmary.

Smith described the process of tanning during an anatomy lecture:

“the skin was undergoing the process of tanning in an adjoining tub – I received the materials and instructions for the process from the Sheriffs, both Tanners. The skin was also dressed at Bedminster, previously to being sent to Essex for the purpose of forming the covering of this book.”

It contains notes collected by Smith on the trial as well as sketches of Horwood and the bill for the binding of the book.

The Horwood Book has been held for many years at Bristol Archives, although over time, it has become too fragile to be handled. You can see the book on display at M Shed and view a digitised version in the searchroom at Bristol Archives. If you’d like to find out more, the reference number for the volume is 35893/36/v_i.

Dr. Richard Smith Junior’s Collection

Smith was a collector of unusual and often macabre objects, among them death masks of hanged criminals, which he made himself.

Much of his large anatomical collection was inherited from his father, also a surgeon, and he used it for lectures at the Philiosophical and Literary Society at the Bristol Institution.

He also collected objects from around the world, including clothes and weapons from Native North America, and taxidermy.

Part of his collection is now at Bristol Museum and at Bristol Archives, some of it was donated to Bristol Infirmary.

Have a look through the collection on our online collection search.

Dr Richard Smith Junior’s Collection

Richard Smith was a collector of unusual and often macabre objects, among them death masks of hanged criminals, which he made himself, and the account of a murder trial, bound in the skin of the young man found guilty and hanged. Much of his large anatomical collection was inherited from his father, also a surgeon, and he used it for lectures at the Philiosophical and Literary Society at the Bristol Institution. Smith Junior also collected objects from around the world, including clothes and weapons from Native North America, and animal remains- often with deformities.

In 1827 the museum was institutionalised within Bristol Royal Infirmary. Smith Junior and surgeon Richard Lowe donated their prepared collections and books. It was open in the west wing of the Infirmary for additions, viewings and lectures. It displayed medical specimens, which served as a status symbol for Smith and the memory of his father. Few of the human remains are associated with names, more usually they were labelled with the surgeon who worked on or collected them.

In 1860, a purpose built museum opened, below Fripp’s Chapel, part of Bristol Royal Infirmary. It was an opportunity, since Smith had died in 1843, to rearrange specimens. This museum also contained microscopes, reference books, and photography facilities.

Part of Smith’s collection is now at Bristol Museums, some remained at Bristol Infirmary. Some of the human remains were buried (such as the skeleton of John Horwood in 2011, 190 years after he was executed) or destroyed. Smith’s paperwork can be viewed at Bristol Archives.

![Mr Yeomans at his Disinterment, 1814 [Robert Yeamans] (drawing/watercolour)](https://ciim-public-media-s3.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/bristol3/large_M2793_1250x1250.jpg)