The Bristol Institution and Mary Anning, a pioneering palaeontologist

Posted on by Lauren MacCarthy.

By Deborah Hutchinson, Curator, Geology

‘The tide warns me I must leave of scribilling’

Portrait of Mary Anning with her dog Tray, Natural History Museum, London. Wiki Commons.

In May 1821 Mary Anning (1799-1847) of Lyme Regis found the first fossil donated to the Museum of the Bristol Institution. It was a well-preserved specimen of a marine reptile called an ichthyosaur.

Anning knew many of the active members of the Institution through their interest in the fossils she found, collected and prepared. She had close links with the Bristol Institution – a major centre for fossil research at the time. Anning made her living finding and selling fossils, many of which were new to science. She understood the scientific as well as the financial value of her finds. She was knowledgeable about fossils and corresponded with leading geologists of the time.

The film ‘Ammonite’ is inspired by Anning’s life; it has generated new interest in her achievements. This blog aims to celebrate Anning’s link with the Bristol Institution through some of the important specimens she found that came here.

Mediterranean Coastal Scene or Capriccio of the Cobb, Lyme Regis, 1857. By James Baker Pyne (1800-1870), BRSMG K1096

The Bristol Institution was founded in 1823. It played a significant role in the early development of palaeontology, the study of fossils. All the early curators were palaeontologists and the museum of the Institution was full of geological specimens. Anning sold many fossils to the Institution. Some were also donated by Members who had bought them from her. A group of Institution members, including the geologists William Daniel Conybeare (1787-1857) and Anning’s childhood friend Henry Thomas De la Beche (1796-1855), bought the museum’s first fossil from her and donated it to the museum in 1823.

The Bristol Institution was also the first scientific ‘home’ of another marine reptile discovered by the Anning family. They found the first complete plesiosaur fossil at Lyme Regis in 1823. Conybeare first announced the discovery to the world at the second Institution meeting in 1824. Anning’s friend De la Beche was not present that evening to hear the announcement as he was away on his plantation in Jamaica. The wealth of many early Members and donors associated with the early Institution came directly or indirectly through transatlantic slavery or colonial sources.

The Bristol Institution in 1825, attributed to Alfred Montague (about 1811-1887), BRSMG K4539.

Fossil Seller, attributed to George Cumberland Senior (1754-1848), BRSMG K3082/041

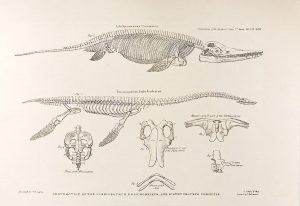

Reconstruction of an ichthyosaur based on the first fossil donated to the Bristol Institution (BRSMG Cb2465). It was lost to bombing in 1940. The first complete plesiosaur is now in the collections of the Natural History Museum, London. Image from Conybeare, 1824.

‘…the Society has thus been honoured by the first public communication respecting it. This hitherto unknown animal was lately discovered at Lyme, by Mary Anning, and, at the recommendation of Mr. Buckland, has been purchased by the Duke of Buckingham’ Gentleman’s Magazine, 1824. Image from Conybeare, 1824.

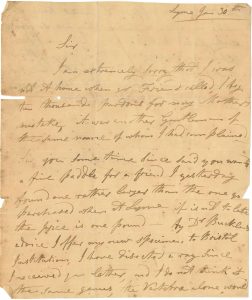

It wasn’t just marine reptiles that Anning discovered at Lyme Regis. In about 1829 she found something else new to science. Bristol Archives holds a very special letter written by Anning to the first curator of the Bristol Institution, John Samuel Miller (1779-1830). In the letter, dated Jan 30 [1830], Anning writes that she will offer any new specimen she finds to the Bristol Institution. The letter contains Anning’s description of this new fossil; she had the knowledge and skill to recognise that it was totally new.

The fossil was bought by John Naish Sanders (c.1777-1870) for around £50. He then donated it to the museum in 1831. In 1833 Henry Riley (1797-1848) described it as something between a shark and a ray and he named it Squaloraia (meaning ‘shark-ray’). Only the body of this fossil ever came to Bristol the tail later went to Oxford Museum of Natural History. Unfortunately the body (BRSMG Ca7106) was destroyed in the bombing raid of 1940.

In her letter Anning writes:

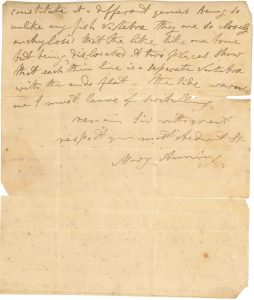

‘…by Dr Buckland’s advice I offer any new specimen, to Bristol Institution, I have disected [sic] a ray since I received your letter and I do not think it the same genus, the Vertebra alone would constitute it a different genus being so unlike any fish vertebra They are so closely anchylosed that the like like [sic] one bone but being dislocated at two places show that each thin line is a seperate [sic] vertebra with the ends flat – the tide warns me I must leave of scribilling [sic]’ ‘Bristol Archives 32079/43/1’

A letter in Anning’s handwriting to J.S. Miller, first curator of the Bristol Institution. Bristol Archives ‘Bristol Archives 32079/43/1’

Back of letter

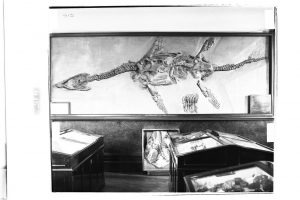

Bristol Museum is still home to one of Anning’s earliest fossil discoveries. This magnificent fossil, shown below, is thought to be the second significant specimen collected by Anning from the cliffs at Lyme Regis in the winter of 1813. This means she was just 14 at the time of its discovery. It is the back part of the skull of a large ichthyosaur.

The Bristol collector James Johnson (1764-1844) bought the fossil for 10 guineas. After his death it was auctioned and John Naish Sanders outbid the British Museum and bought the specimen for the Bristol Institution where it survives today in the collections of Bristol Museum & Art Gallery.

The back portion of the skull of a large ichthyosaur (BRSMG Cc940) seen below the wall mounted fossil Atychodracon (BRSMG Cb2335), destroyed in the bombing raid of 1940. Image taken from the museum’s second home, now the restaurant Browns.

The large Anning ichthyosaur skull in the Geology Library today at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery

Bristol Museum & Art Gallery is lucky to have close connections with such a pioneering palaeontologist. As a woman Mary Anning was barred from formal scientific life, while the men around her benefited from her expertise and finds. This blog acknowledges and celebrates her contribution to geology and the geology collections formed at the Bristol Institution.

References

- Conybeare, W. D. 1824. On the Discovery of an almost perfect Skeleton of the Plesiosaurus. Transactions of the Geological Society of London, S2, 1, 381-389

- Sharpe, T. 2021. The Fossil Woman: A Life of Mary Anning. The Dovecote Press.

- Taylor, M. A. 1994. The plesiosaurʼs birthplace : the Bristol Institution and its contribution to vertebrate palaeontology. Linnean Society of London, Zoological Journal, 112:179- 196.

- Taylor, M. A. and H. S. Torrens. 1987. Saleswoman to a new science: Mary Anning and the fossil fish Squaloraja from the Lias of Lyme Regis. Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society 108:135–148.

- Torrens, H. 2008. A Saw for a Jaw. The Geological Society.

2 comments on “The Bristol Institution and Mary Anning, a pioneering palaeontologist”

Hi I Walter Reed, great grand children of Edwyn C. Reed born in Bristol 7/Nov./1841, and dead in Chile 5/Nov./1910. He created in Chile 5 Natural Histoy Museums. I have a origi9nal letter to him, from Mr. John Naish Sanders, tell: “I have the honour to tell you thanks for your present of 55 speciments of coleopteras….” (October 1oth. 1864).

I want investigate the life of him in Bristol. I know you have a couple of documents of him, his records in the institution, addres etc. To pre÷pare my second book of him: Lok in internet: “Edwyn C. Reed y el archivador rojo”. Is very important to me. I am doin a visit to you when I can. Thanks

Walter Reed (See as well “Edwyn C. Reed”, in internet…

Hi Walter, thanks for getting in touch with information about your great grandfather Edwyn C. Reed. The museum does indeed have him recorded in our Donation Book (donation number 2785) as having donated ‘A Series of 55 Specimens illustrating 24 species of British Coleoptera found in the neighbourhood of Bristol.’ Please do get in touch with me directly if I can assist you with anything regarding your grandfather.