In search of sea monsters

Posted on by Fay Curtis.

Bonnie Griffin, Natural History Curator

In 2017, for the first time ever, the museum is holding an exhibition focusing on our incredible Pliosaurus fossil, found in Westbury in 1994. This massive marine reptile was 8 meters long, had teeth the size of steak-knives and was the apex predator swimming the Jurassic seas that once covered Bristol.

To have a ‘real’ sea monster preparing for display is an exciting time for the Natural History team and the scientists, mainly based at the University of Bristol, who have been studying the fossil.

Tooth from the Westbury Pliosaur II (Pliosaurus carpenteri)

With this exhibition in mind, I began spotting sea monsters lurking in the wonderful collections at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery. Sea monsters are usually portrayed as large, fabulous, extraordinary animals of the sea, but often devouring people and bringing bad luck or destruction.

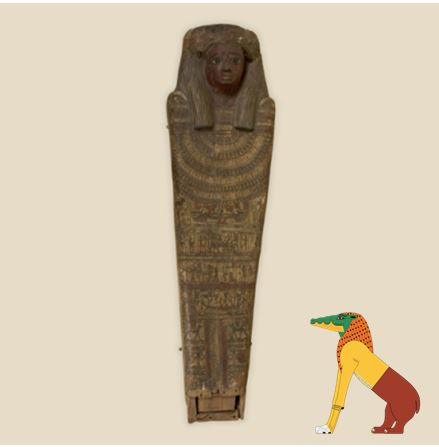

The first stop is the Ancient Egypt Gallery to look at the beautiful decorations on the 2,300 year old wooden coffin lid of Paty-Hewty.

If you look for the scales of justice, nearby you’ll find the female demon Ammit.

Part lion, hippo and crocodile, she devours the unjust hearts of the dead after they’re weighed against the feather of truth.

Certainly she has ‘fabulousness’ in her look and a man-eating nature, undoubtedly making her a monster, but being two thirds freshwater animal, she’s not one of the sea.

Heading to Gallery 6, Art Curator Jenny Gaschke pointed out the Fisherman and the Syren (Siren) by Lord Frederic Leighton.

The half-bird half-woman monsters from Greek mythology are analogous to the mermaids who share their beauty and chimeric nature. ‘Modern’ mermaids are sometimes portrayed as helpful heroines, but originally they were more sinister, luring sailors to dangerous waters and ultimately to their deaths. In Leightons painting, the fisherman will be lucky if it’s just his fish he loses! Although her embrace looks initially tender, the siren’s fishy tail ominously wrapped around his leg reveals his terrible fate.

Although monstrous in nature, mermaids and sirens aren’t known for eating the men they doom and are of normal size, so the search continues for our classic sea monster.

On the first floor balcony is the sea dragon’s gallery where a giant pliosaurus skull sits alongside the beautifully preserved ichthyosaur fossils.

With ’fleshed out’ models showing the complete animals, images nearby reveal how big these Jurassic reptiles grew.

They certainly appear huge, monstrous and extraordinary – unlike anything in the sea today – but remember these were once ‘real’ animals; with breathing lungs and beating hearts.

We don’t know their temperaments or detailed specifics of exactly how they looked but scientists can infer their likely appearance using comparative anatomy techniques and making evidenced based deductions by looking at their bones. Even for a scientist, reconstructing the soft tissues of these animals allows for a little creativity to fill in the blanks.

These Jurassic giants were (thankfully) not man-eaters, with humans evolving over 60 million years after the last sea dragons went extinct. All we have now as evidence is their fossilised remains, but these aren’t the only sea creatures to have been turned to stone…

Gallery 2 houses a fantastic beast in Moreau’s 1870 painting of Perseus and Andromeda.

After her mother, Queen Cassiopeia, boasts that Andromeda is more beautiful than the sea-nymphs, an enraged Poseidon sends a sea monster, Cetus, to bring destruction to their lands. On advice from an oracle, her parents offer poor Andromeda as a sacrifice, but thankfully Perseus hears of her plight and steps in to kill the monster.

In the painting we find Cetus, fantastic in size and fabulous in composition, writhing his snake-like coils and fishy tail as he approaches Andromeda to devour her. Perseus, brandishing the head of the gorgon Medusa, uses her famous glare to turn Cetus to stone.

Although Cetus is depicted as a rather reptilian and fishy monster here, his moniker is familiar to me as a natural historian; the mammal clade that includes the great whales is named Cetacea after him. Cetus lives on today in this group which containins the largest animal ever to have lived on Earth; the blue whale. Measuring 30 meters and 200 tonnes the blue whale is monstrous in size but not in nature, in fact, this colossal krill-eater is a vulnerable, endangered species.

Next time I’ll be digging through the off-show collections to see what other sea monsters are lying in wait!

Pliosaurus! opens Saturday 17 June at Bristol Museum and Art Gallery.