Rediscovering Black Portraiture: The Young Catechist by Henry Meyer

Posted on by Saffron Smolka.

By Peter Braithwaite, baritone, artist, broadcaster and writer.

I made this recreation of the painting ‘The Young Catechist’ by Henry Meyer for my exhibition at the museum, Rediscovering Black Portraiture. I’ve reworked Meyer’s 19th century image of a praying African man. I am on the Royal Palm fringed driveway of Codrington College, Barbados. I’m wearing a red Harrington jacket and holding a photocopy of a photograph of my ancestor Gladys Brathwaite. Gladys was the illegitimate granddaughter of Reverend John Brathwaite (1777-1856) and a formerly enslaved woman named Ann Goddard (c.1790-c.1892).

My great-great-great-great grandfather Edward (Addo) Brathwaite (1742-1831) was forcibly converted to Christianity during his enslavement in Barbados. Like Addo, the African man in Meyer’s painting’s most deeply held beliefs – and his very identity – were transformed through his encounter with European culture.

This recreation explores the history of Christianisation in my own family.

Recreation of a painting of The Young Catechist by Henry Meyer as part of the Rediscovering Black Portraiture exhibition

I have a personal connection with Codrington College. The enslaver John Brathwaite (1722-1800), my six-times great uncle, was the lessee of the Codrington Estates. These were plantations owned by the Church of England’s missionary arm, The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. These two sugar estates generated more than £5 million in today’s money per year. Like the cattle and horses on the estates, Africans enslaved at Codrington were branded with the word “SOCIETY” on their bodies. When they died from disease, injury or overwork, they were simply replaced. As Barbadian historian Sir Hilary Beckles points out, from the beginning of the 19th century, the Church of England defended its right to own and brutalise enslaved Africans, claiming that enslavement was “Christian”.

My formerly enslaved four-times great grandparents, Edward Addo Brathwaite and Margaret Brathwaite (1780-1860), were Christianised on the Codrington Estates. Edward Addo began life as the property of John Brathwaite, freed aged 73 for ‘good conduct’. Extraordinarily, Edward Addo, his wife Margaret, and their eleven children are mentioned by name in the Papers relating to Codrington College, Barbados, and in the Annual sermons and reports, from 1702 on. They attended the Society Chapel, which was created for enslaved people on the Codrington Estates. They were held up as role models. This separate chapel for the 300 Africans enslaved at Codrington was part of the Church’s project to “promote the gradual civilisation” of the enslaved population. While abolitionists campaigned in Barbados and the UK (the “Mother Country”) the conversion to Christianity helped to keep the peace.

“The Chapel was at Easter very much crowded; thirteen coloured persons were communicants, and at Whitsunday there were eighteen. Amongst these was a very respectable and well-disposed free coloured family, who had, from the convenient site of the chapel, become regular attendants. These I supplied with books; and at their request, imported a copy of Bishop Mant and D’Oyley’s Commentary on the Bible. The head of this family is Edward, or Addo a slave formerly of the late Mr. John Brathwaite, the munificent upholder of the Society’s plantations at the period of their almost entire ruin.”

Taken from the 1823 entry of A sermon [on Matt. xxviii. 19, 20] preached before the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel of the Gospel in Foreign Parts at their Anniversary Meeting in the Parish Church of St Mary-le-Bow in 1829.

Addo Brathwaite was born in around 1742, probably in Ghana. He was captured, sold and forcibly transported to Barbados where he was enslaved on one of the sugar plantations owned by the Brathwaite family. He started as a field worker, progressed to the status of domestic servant and was freed for “good conduct” at the age of 73. The Brathwaites gave Addo their surname. Addo’s freedom papers (or manumission papers), were signed off by catechist John Hothersall Pinder.

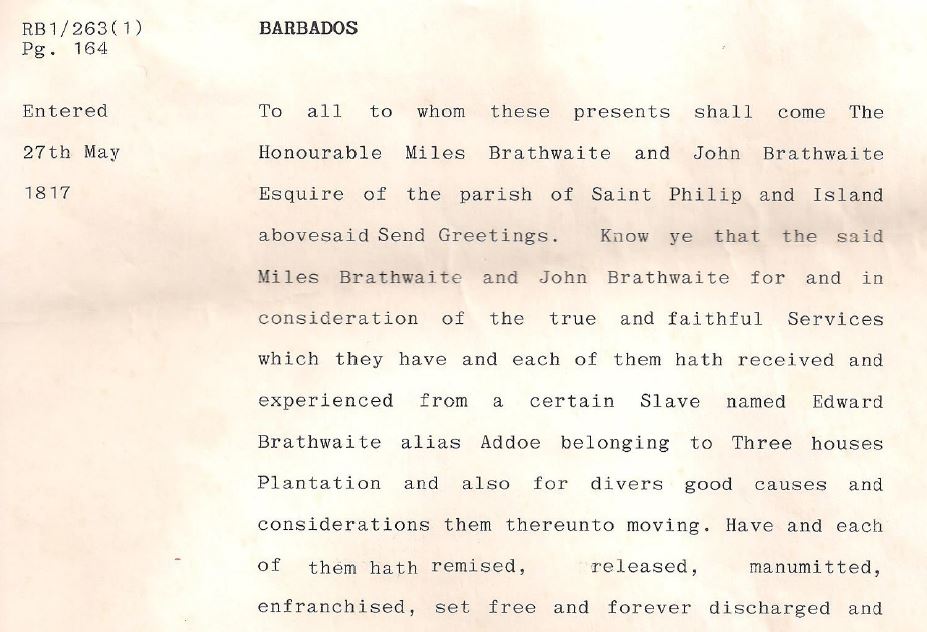

Text excerpt from manumission (release from slavery) papers from 1817 relating to Addo.

His freedom for “good conduct” so soon after the 1816 insurrection in Barbados raises questions about whether he was rewarded his freedom for protecting his white Brathwaite enslavers.

Margaret was born in 1790 on the Caribbean island of Barbados. She was the illegitimate daughter of the Hon. Miles Brathwaite II, a prominent white enslaver. The identity of her enslaved African mother is not yet known. We might assume she was enslaved on the Brathwaite plantation. Margaret’s mixed heritage gave her a marginal advantage in Barbados’s rigid racial hierarchy – she was granted full freedom as a teenager, and received an education.

As a free Black family in pre-emancipation Barbados, Margaret and Edward Addo Brathwaite were granted some privileges but denied most. For freed people, becoming Christians meant spiritual gains of faith. The chance to be “British, Christian and a loyal subject” also supported the claims to civil rights in a society where they were neither enslaved nor entirely free. For example, Edward Addo and Margaret would not have taken communion alongside white Anglicans. It is more than likely that these unwritten rules are what led them to the congregation at Society Chapel.

In my exhibition I have included the transcript of a letter written by Margaret. The original is said to believed to be in a vault in a church in St Philip, Barbados.

On the 2nd July 1821, having been visited at home by the catechist Reverend John Hothersall Pinder, Margaret wrote this letter to celebrate her family’s official conversion to Anglicanism. She set out a charge for her family to celebrate a Brathwaite family festival on July 2 every year. Margaret’s descendants have celebrated this Family Festival every July 2 since. The Festival starts with the hymn, followed by prayers and readings. Margaret’s letter is then read followed by a roll call of all descendants who are asked to share a scripture, verse, prayer, poem and in recent years any reflections. The event is followed by a delicious feast.

In many ways, Margaret’s literacy serves as a portrait of her. It is one of the few surviving sources written by a freed woman of colour in early 19th century Barbados. Yes, it illustrates her strong religious beliefs but also shows what her early freedom meant to her – the year she wrote her letter there were nearly 80,000 men, women and children enslaved in the colony of Barbados. In the capital of Bridgetown, enslaved people who had tried to escape were confined to an outdoor public holding cell known as The Cage. They waited there until they were claimed by their owners or tried. This reality is probably what prompted Margaret to choose ‘Hark, my soul! it is the Lord’, with words by the anti-slavery poet William Cowper as the Brathwaite festival hymn. A bold choice that could represent an act of resistance in an oppressive society.

In July 2022, I visited the Society Chapel (now the Church of the Holy Cross) on the Codrington Estates in Barbados. I have included a recording of the choir and congregation of the Church singing the Brathwaite Family Hymn in the exhibition. Many of the congregants singing here are, like me, descendants of the enslaved catechumens who once worshipped at the Chapel.

Recreating the Young Catechist was a way for me to connect with my own history and make space to consider the Black life at the heart of Henry Meyer’s painting.

Find out more

- To find out more about this exhibition currently at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery visit Peter Brathwaite: Rediscovering Black Portraiture.

- You can order a copy of the Rediscovering Black Portraiture book from the Bristol Museums Shop.

- Further information on Peter Braithwaite and his photographic recreations of artwork can be found in this Guardian article -‘Cooking oil, Grandpap’s cou-cou stick and a quilt – how I recreated Black portraits and celebrated the stories of people of colour’

- You can also listen to Peter talk about his work on BBC Sounds to Saturday Live and also BBC Sounds Arts and Ideas