Creating Deadly Doris

Posted on by Fay Curtis.

By Tony Hitchcock, model maker

Doris the Pliosaurus, ferocious star of our recent temporary exhibition, now has a new long-term home in the back hall at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery thanks to visitor support and funding from our Friends’ Group – Friends of Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives and Bristol Museums Development Trust .

To celebrate her arrival, we asked Tone Hitchcock, model maker, to share the journey of how she was made.

A Skull

I first met Doris nearly three years ago, when I was asked by Bristol Museum & Art Gallery to make a life-sized replica of her skull for Cheltenham Science Festival.

For a palaeo-nerd like me, it was something of a dream come true. I got to poke around in the stores, taking photos and measurements, making sketches and rough models of her bones, all before she had been seen by the public.

Initially, I made a very small maquette- a 3D sketch in modelling clay, working closely with Dr Judyth Sassoon, who helped me to understand the complicated engineering of the Pliosaur’s structure.

Once this had been approved, I started work on the skull, scaling up from Judyth’s drawings and the maquette, and carving it from high-density polystyrene; one of the most commonly used materials for prop making.

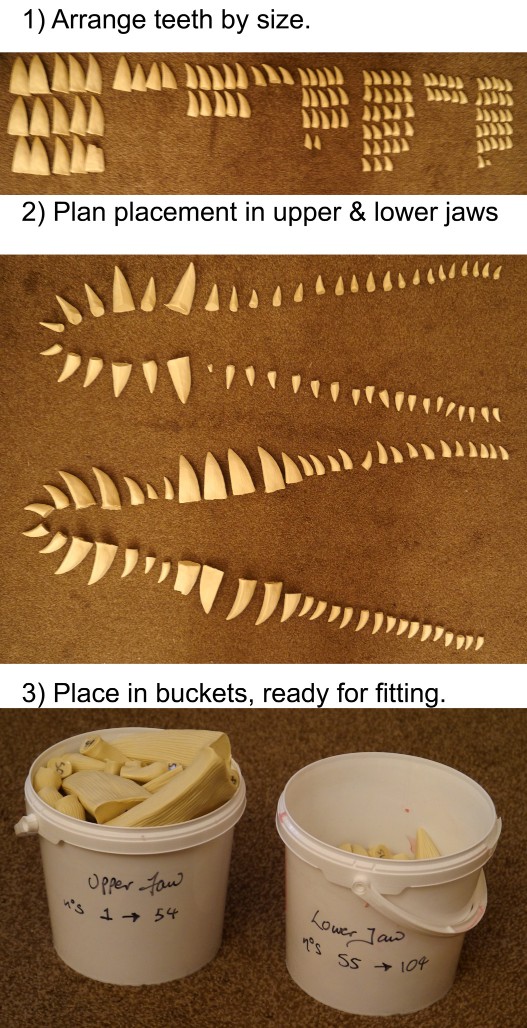

The next stage was the teeth; 154 of them, in varying sizes from six inches to one inch.

Fortunately for me, Pliosaur teeth are not bi-curved; they curve inwards, but not backwards.

This meant that I could use the same tooth shape for each side of the jaw, top and bottom.

I made five initially, using a polymer clay. Then I made silicone moulds from them so that I could cast them all off.

This took some time, and used up most of my kitchen table (I have a very patient wife).

After this was the even more time consuming job of arranging them into the right order and fitting them all in place- embedded deeply so that they would survive being handled by the public.

I then coated the skull with glassfibre tissue and Jesmonite resin. This adds a tremendous amount of strength, and a bone-like appearance when it is set.

The final layer of artworking was achieved with acrylic paint dry-brushed onto the surface of the bone, and the teeth.

We wanted the skull to look as it would have done before the fossilisation process altered its colour.

I’ll admit, I got some funny looks in the supermarket car park when I had to stop in there on the way up to Cheltenham; I suspect some people thought I had the remains of a giant croc in the boot!

She made it up in one piece, though, and finished the Festival as the centrepiece of a question and answer session with Isla Gladstone and Debs Hutchinson from Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, BBC natural history presenter Dr Ben Garrod, and myself.

The living creature

During the process of making this skull, we vaguely talked about the possibility of building the postcranial section of the skeleton so that the whole thing could be exhibited in Bristol Museum. That idea evolved: as we already had the actual skeleton which could go on display, why not concentrate on a life size reconstruction?

Fortunately, I have some friends who live in a gorgeous old house in South Stoke that used to be a brewery; they offered me one of their enormous undercroft tunnels to use as a studio, which afforded me the perfect space to construct the creature.

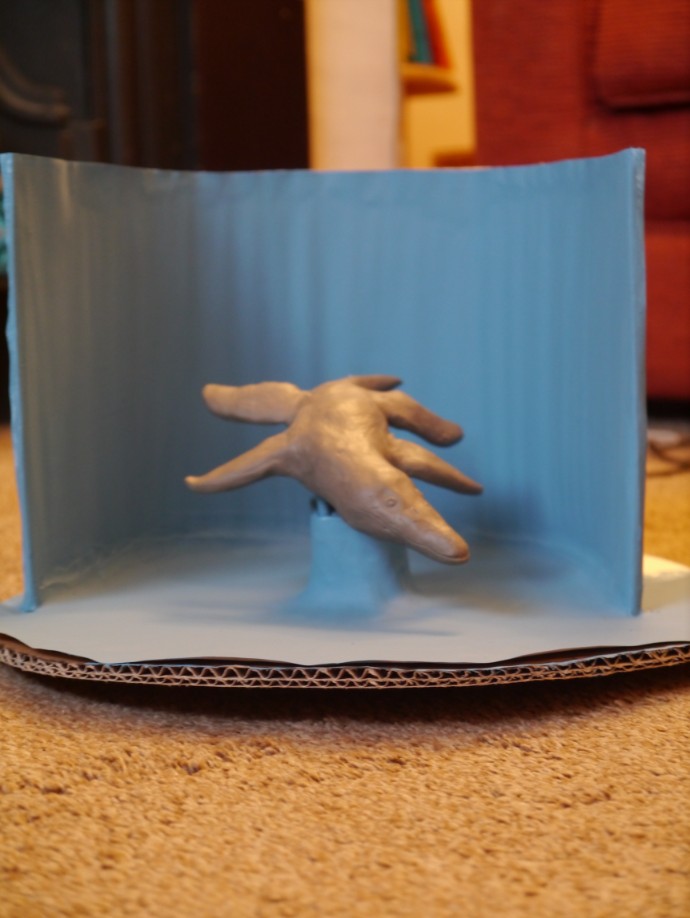

The first stage in the construction of Doris was a little easier to manage. As with the skull, I started with a maquette; initially, this was in sculpting wax, so that the museum staff and I could manipulate it freely until we arrived at a pose that we were all happy with.

The maquette that I made had to be very accurately sized, otherwise we would not have been able to get her through the doors and into the museum. I checked, re-checked, and triple checked all of the measurements, but it was still my main worry for the project.

One of the more vexing questions about Pliosaurs is what their outer covering would have been like.

There is evidence from a related species that their skin was leathery and scale-free. However, during the sculpting process, a new specimen, was discovered in Mexico that appeared to preserve very fine scales on at least some areas of its skin.

We decided that the best option was to slightly split the difference.

There were various different options that we tried for her colour scheme, all based around marine predators, which show countershading, and often have blotchy patterns that help to further break up their outline. One of the main points of the original brief was that she needed to have a strong visual presence, so that she would be recognisable as Bristol’s own Pliosaur.

We looked at Tiger Sharks, Dusky Dolphins, Spinner Dolphins, Common Dolphins, Orcas and even penguins to come up with our version.

We also added scars from her food, and various wounds from fighting, using pictures of Squid-scarring on Sperm Whales, and shark bites on dolphins as reference.

The process of actually making full-sized Doris is, on paper, fairly simple: we took a laser scan of the maquette in order to produce a 3D file, which was then used to form her out of blocks of high density polystyrene.

Once we’d worked out how she fitted back together, we then had to fit a scaffolding truss inside, which would support an internal speaker which would give her a heartbeat and grumble, and provide socket points so that we could attach her flippers once she was in the museum: if we attached the flippers on permanently, she wouldn’t have fitted through the front doors.

I worked on her head at home, casting and fitting teeth from the moulds that I already had from creating the skull model two years previously, and creating enough room in her cranial area to fit the animatronics for her eyes.

I worked on her head at home, casting and fitting teeth from the moulds that I already had from creating the skull model two years previously, and creating enough room in her cranial area to fit the animatronics for her eyes.

The next stage, after six weeks or so of painstakingly taking her apart, hollowing her, fitting the truss, and re-assembling her again, was to shoehorn all the pieces back into a removal van, and take her back up to Hampshire to have the tough spray surface applied.

When Doris arrived back at the museum, we all stood around for a while trying to work out exactly how best to manoeuvre her in.

In the end, we all just laid hold and manhandled her up the stairs, through the entrance, and into the hall. It took 13 of us to do this and for the doors to be removed from their hinges.

My team and I then had a week on site to fit her flippers, the speaker, the animatronics and finally to paint her. She was almost ready to meet the public.

The final part for me was watching the installation of the projections that my friend Damir Martin had created so that Doris had other creatures to swim around her.

The toy

There comes a point in any child’s life when their ultimate dream is to create their very own toy. There comes a point in any adult’s life where that dream must, reluctantly, be put to one side. Doris allowed me to pick that fantasy up again, and my seven year old self could not have been more delighted.

We decided that we would go for a 1:32 scale for the toy, as this would mean that we could keep it within a reasonable pocket-money price bracket.

I was fortunate to have a ready-built focus group in the house, in the shape of my two boys, who are currently seven and ten. As we already had the 3D computer file of the original maquette, we had a great starting point, but the focus group raised a very interesting point: I sculpted the maquette to make it as dynamic as I could, caught in the act of banking after potential prey. This would have given us a toy that was curving to the left, and neither of the boys were happy with that.

They pointed out that, when playing with a toy like this in the bath, this would limit your imaginary options, as it would forever be turning, and they wouldn’t be able to make it swim where they wanted it to go. So we decided to straighten out the scan.

Slightly less easy to sort out was the mouth: we needed the toy to have a nice toothy gape, and the original maquette has its gob firmly shut.

I created the teeth from toothpicks, and from barbecue skewers for the larger ones, taking care to match them as closely as possible to the actual dentition of Doris; I even sculpted the abscess on her palate and the internal nostrils into the tiny model.

Unfortunately, these teeth proved too tiny for the laser scan to pick up properly, so they had to be digitally sculpted directly onto the 3D file, using the 3D printed model as a reference point. This file was then sent on to China for the manufacturers to produce their moulds.

And here she is, available to buy from the Bristol Museums shop.

So, there you have it. Over two and a half years work to bring to life a creature that last swam over Bristol some 150 million years ago, when most of the South West of England was covered with a shallow tropical sea.

From start to finish, working on the various incarnations of Doris has been an absolute joy; the Museum staff have been fantastic to work with, and I sincerely hope that we can do something similar again together in the future.

Truthfully, the whole thing was something of a dream come true, particularly for someone like me who has been a Palaeontology nerd for as long as I can remember; of all the weird and wonderful things I’ve made over the years, this remains my absolutely favourite project.

With thanks to

My construction/artworking and installation team:

- Gwilym Hitchcock

- Giz Hitchcock

- Sarah Dowling

- Dan Collison

- Brendan Arnold

- Emma Powell

- CNC Polystyrene

- Barry Hudson of Flint’s Theatrical Chandlers

My toy focus group:

- Jacob Q Hitchcock

- Lukas C HItchcock

Browse those who dared to meet Deadly Doris on our Pinterest page.