A potted history of soap making in Bristol – until 1954

Posted on by Fay Curtis.

By Lee Hutchinson, curator of history

Bristol has laid claim to several firsts in English history. One of those is soap manufacturing. In the 1815 edition of the Bristol Guide, the author echoed the belief that

“the first manufacture of Soap in England was in Bristol”.

As did historian Thomas Fuller. In his 1662 Worthies of England, he declared that Bristol was making soap long before London:

“I behold Bristol as the staple place thereof, where alone it was anciently made”

It was his view that before the 1500s “the land was generally supplied with Castile [soap] from Spain, and Gray-soap from Bristol…much the cheaper.”

And over 400 years before Fuller, in the 1190s, a monk by the name of Richard of Devizes wrote:

“In Bristol there is no one who is not, or has not been, a soap boiler”.

[For Latin enthusiasts, the actual words attributed to him are: “Apud Bristollum nemo est qui non sit vel fuerit saponarius”]

The monk’s chronicle is laced with caustic humour. It seems safe to assume that not everyone in Bristol was a soap boiler.

The Proceedings of the Company of Soapmakers (1562-1642) is, arguably, a more reliable source of information. It contains the names of people involved in the city’s soap industry. And there are over 180 of them – mostly men and a fraction of women – often widows who had taken on their late husband’s business. In all probability no more than 50 or so would have been active at any one time. Throughout the Middle Ages and up until Victorian times, soap making was a cottage industry.

So what kinds of soap were being made at the time of the Proceedings? There seem to be differing accounts about the ingredients. Among those mentioned are ashes, tallow (animal fat) and all manner of oils, including vegetable oil, rape oil, train oil (from whale blubber) and olive oil. Two types in particular are described: one that was soft, black and sold in pots, “commonly called Bristoll Sope”; and another, a “grey soap” that was supplied in large quantities to London.

By the mid-1500s, Bristol soap boilers were importing olive oil from Spain. It became the staple ingredient in Bristol soap. And the industry flourished – until the 1630s. In 1632, King Charles I granted a monopoly to the Society of Soap-makers of Westminster. This gave the Society the exclusive right to manufacture a standard soap made only of the “raw materials of the kingdom” – at a cost – of £4 per ton produced, payable to the crown.

“The fiscal benefit to the crown from monopolies was considerable,” wrote historian Christopher Hill, “but it could not compare with the injury done to the consumer and industry by the rise in prices.”

The Society had the authority to regulate soap production. By 1636, Bristol’s output had been limited to 600 tons per year. According to author John Somerville, this represented a cut of up to 70%. The soap monopoly, he contended, led to “the destruction of Bristol’s soap industry.”

It wasn’t until the mid-1700s that two notable soap manufacturers emerged: Farrell, Vaughan & Co. in 1743; and Samuel Fripp & Co. in 1745. The latter underwent several name changes. In 1783, the company expanded to Broad Plain, in the St Philip’s area of Bristol, on the east side of the River Avon.

By the 1820s, Bristol was once again one of the country’s leading soap manufacturers. Its annual soap output of approximately 3600 tons was surpassed only by Liverpool (8500 tons) and London (15,000 tons).

In 1841, Fripp & Co. merged with Welsh merchants Thomas Thomas and Christopher Thomas. They became Thomas, Fripp & Thomas. The Thomases had set up in Bristol during the early part of the century. They were a father-and-son-run firm of soap and candle makers.

Fripp & Co. had specialized in soap for personal use made with olive oil (‘toilet soap’), the Thomases in soap for household use made with tallow. Thomas, Fripp & Thomas combined their skills to produce both types at Broad Plain, though the household variety was their main product.

When Edward Bowles Fripp Jr. retired in 1855, the company became known as Christopher Thomas & Brothers. Soap duty and various soap-manufacturing regulations were scrapped in 1853. This led to what has been described as the Thomases’ “golden years”, from 1856 to 1889.

With business booming, from 1865-67 the Broad Plain soapworks underwent extensive redevelopment. During 1881-82 they were re-built by Charles Thomas, the youngest of the Thomas brothers. He visited Florence in 1881 and was captivated by the city’s architecture. On his return, he had the buildings recast in the Florentine style. This included the addition of chimneys that looked like corner turrets and a crenellated parapet on the top of the pan building (where the soap was boiled). These features emulated the design of Florence’s town hall – the spectacular Palazzo Vecchio.

In the later 1880s, profits began to decline – largely because Christr. Thomas & Bros were unable to compete with rivals in London and Liverpool. Their main competitors were the Bolton-born Lever Brothers.

They had an exceptional product in Sunlight soap. This was the world’s first packaged and branded laundry soap. It was made with glycerine and vegetable oils. In many homes, it was used as a ‘one soap for all’.

Christr. Thomas & Bros attempted to see off the competition. In 1898, they launched a similar product – an olive-oil based (and latterly green) laundry soap called Puritan. But their profits continued to decline and in 1912 they sold out to Levers.

Lever Brothers recognized the role of creative marketing in gaining competitive advantage. At the turn of the twentieth century they were spending over £100,000 a year on advertising.

By 1914, Levers were producing almost a third of the country’s soap at their Port Sunlight works. They modernised the works at Broad Plain. Sunlight maintained its position as the country’s leading brand. They continued to produce Puritan under the Christr. Thomas & Bros name, as it had a heathy share of the market in the South West.

When the country was struck by the 1918 flu pandemic, Levers promoted their soaps as disinfectants to help tackle the virus. Their adverts claimed that Sunlight would place people on the “Highway of Health”, while Lifebuoy ensured “antiseptic cleanliness” against the “influenza scourge”.

Through the 1920s, Levers bought many of their British rivals. By 1921, they were producing more than 70% of the soap sold in England.

After William Lever’s death in 1925, his enterprises were amalgamated. Lever Brothers merged with Dutch margarine producer Margarine Unie to found Unilever in 1929.

In terms of market value, it was the biggest company in Britain. And it continued to expand – not just in the UK but across the world.

Unilever’s brands included Sunlight, Lifebuoy, Lux, Monkey Brand, Pears’, Rinso, Surf and Persil.

Historian John Hunt wrote:

“By the mid-twentieth century soap manufacture in Britain had been substantially consolidated by Lever Brothers into a modern, large-scale manufacturing industry.”

In 1953, Unilever resolved that it was “uneconomical to undertake the necessary modernisation” at Broad Plain, and, in 1954, it closed down the factory.

Images

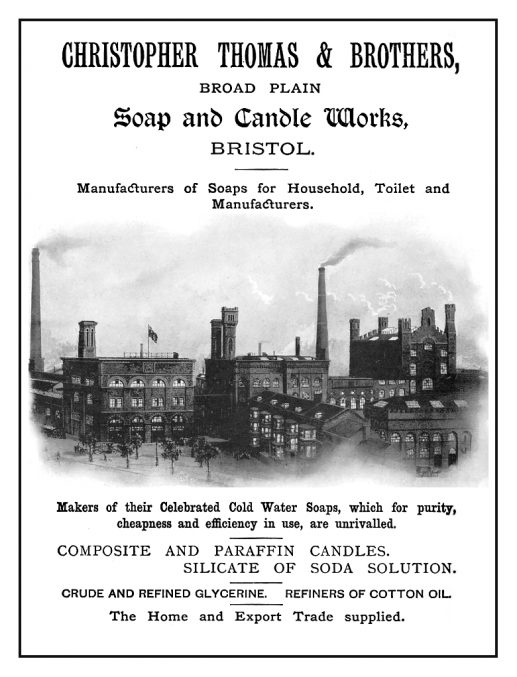

- Advertisement for Christopher Thomas & Brothers, showing their works at Broad Plain. © Unknown

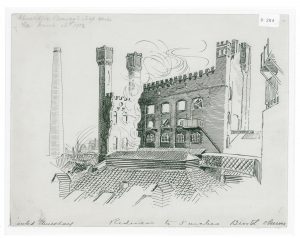

- Samuel Loxton’s print of the ‘Fire, March 16th 1902’ in the old pan building at Christopher Thomas’s Soap Works. Costing over £20,000 in damage, one man was killed by a collapsing wall. © Bristol Libraries

- Double bar of Puritan soap, made by Christopher Thomas & Brothers, 1920s. © Bristol Culture

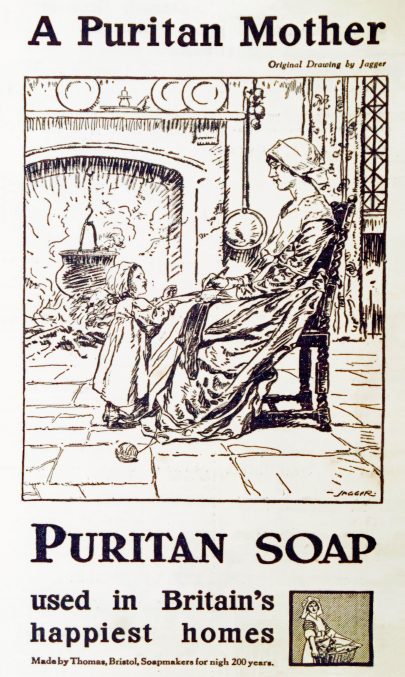

- Advertisements for Puritan soap, 1917 and 1919. © Unknown

- Employees of Christr. Thomas & Bros sheltering from bombing during World War 2 at the Broad Plain soap works. © Bristol Culture, M Shed collection

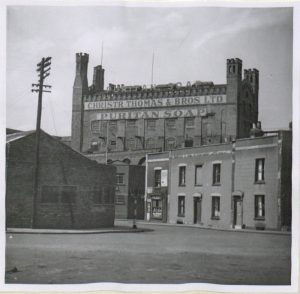

- Christopher Thomas & Brothers’ soap works at Broad Plain, about 1951. Courtesy of Bristol Archives

- Packaged Puritan soap and olive-green bar, made by Christopher Thomas & Brothers, 1950s. © Bristol Culture, M Shed collection

- Cover image: The Bristol soap and candle works in St Philip’s, about 1900, when trading as Christopher Thomas & Brothers. The view shows other businesses and dwellings occupying the south side of Broad Plain. Some of the buildings still stand. Note the ‘Bristol Byzantine’ architectural style. © Bristol Culture, M Shed collection

Further Reading

- Chandler, A.D. and Mazlish, B. (eds.) (2005) Leviathans: Multinational Corporations and the New Global History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Foyle, A. (2004) Pevsner architectural guides: Bristol. London: Yale University Press

- Fuller, T. (1662, abridged edition 1952) The Worthies of England, first printed in London by J.G.W.L. and W.G. Abridged and introduced by John Freeman. London: George Allen & Unwin

- Giles, J. A. (ed) (1841) The Chronicle of Richard of Devizes: Concerning the Deeds of Richard the First, King of England, also, Richard of Cirencester’s Description of Britain. London: James Bohn

- Heath, G. (1815) The Bristol Guide; Being a Complete Ancient and Modern History of the City of Bristol, including a Description of the Interesting Curiosities of its Vicinity. Third Edition [of The New History, Survey and Description of the City and Suburbs of Bristol by George Heath]. “Revised and Considerably Enlarged by Bristoliensis”. Bristol: J. Mathews

- Hill C. (1980) The Century of Revolution 1603-1714. Surrey: Nelson

- Hunt, J. A. (1999) ‘A short history of soap’, The Pharmaceutical Journal; 263

- Latimer J. (1900) The Annals of Bristol in the Seventeenth Century. Bristol: William George’s Sons

- Matthews, H. E. (ed.) (1939) The Company of Soapmakers 1562-1642. Bristol: Bristol Records Society vol. 10

- Penny, J. (2005) Bristol at Work. Derby: Breedon Books Publishings

- Somerville, J. (1991) Christopher Thomas Soap Maker of Bristol: The story of Christr. Thomas & Bros 1745-1954. Bristol: White Tree Books

- Unilever Archives, unilever-archives.com

6 comments on “A potted history of soap making in Bristol – until 1954”

Dear Lee Hutchinson and Charlotte Bartholomew,

I really enjoyed this article.

I am currently working on a project at the University of Bristol looking at the history of postgraduate research. Whilst doing this, we have noticed that a number of PhDs during the 1920s researched soap. These seem to have been supervised by James McBain and included Mary Evelyn Laing, and 7 others.

I was wondering if in your work on this you had come across any links to the university in terms of research in this period. I suspect this research was directed towards this but haven’t been able to find any concrete evidence.

All the best

James

Hi James, thank you for your enquiry and glad you enjoyed the blog post. For further information about the reading and research, I would recommend you contact Lee directly at [email protected] Best regards, Charlotte

Hello,

Fantastic article! Recently I have been researching my family tree. My great grandfather is showing up as a Commercial clerk for the soap works, Bristol 1881. Im just wondering if you have archives that might hold his details? His name was Alexander W Allen. We always believed he had connections with Port Sunlight wirral

, but theres nothing documented to support this, only Bristol. Were the two manufacturers connected at some point? As he lived in Bristol and then later relocated to Liverpool. Any help would be very much appreciated. Kind regards Rachael

Hi Rachael. We don’t have staff or family records at Bristol Museums, and we don’t have the resources to carry out detailed genealogical research, but you could try Bristol Archives https://www.bristolmuseums.org.uk/bristol-archives/contact-bristol-archives/ or Unilever Archives [email protected]

Lever Brothers acquired Christr. Thomas & Bros. Ltd in 1912. It’s possible that your great-grandfather went on to work for them in Liverpool.

Hi Rachael

Did you get a reply to your query? I have a similar interest since two of my ancestors- husband and wife- also worked there

Richard, thanks for your enquiry. Please see my reply to Rachael above.