What inspires our curators?

Posted on by Fay Curtis.

From Monday 23 to Sunday 29 March 2015 it’s #MuseumWeek over on Twitter. So far this week museums and visitors have been sharing tantalising snippets and intriguing information about what goes on behind the scenes in cultural organisations across the globe.

Thursday’s theme is #inspirationMW. This is your chance to share with the world what inspires you in (or about) museums! We thought what better opportunity than to give a few of our curators the chance to tell you about what inspires them from our collection.

Sue Giles, Senior Curator – World Cultures

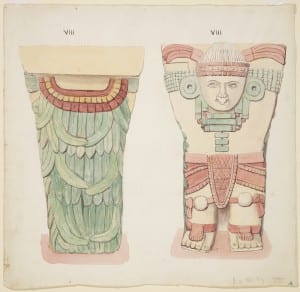

One object that inspires me is this watercolour of a painted stone figure. The inspiration is maybe more from the artist, Adela Breton, who from the 1880s spent a lot of time travelling in Mexico, turning from a tourist to a respected Mexican archaeologist by the 1920s. A talented artist, she painted her way around Mexico, and Bristol inherited her collections when she died in 1923.

Why does this watercolour inspire me? Partly it is Adela Breton herself, a Victorian lady gallivanting about in the wilds of Mexico with a Mexican servant, Pablo Solario, a carriage full of luggage and every illness you can think of. Partly it is the importance of her work – for three sites, the only colour record of lost decoration. Partly it is the privilege of being involved with the collection and making it available to researchers over the years and seeing their excitement as they look at the watercolours. Partly it is that when I took an exhibition of her watercolours to Mexico, the Museo Nacional de Historia had borrowed Caryatid VIII from the Museo Nacional de Antropología. It

stood on a tall plinth in the centre of the gallery, in front of the painting. So although Caryatid VIII is not the most beautiful of the 15 pictures of caryatids, it has a special meaning because it was in ‘my’ exhibition.

The Adela Breton collection (watercolours, photographs and objects) is on our online collection search.

Lee Hutchinson, Curator – Industrial and Maritime History

Around a year ago, Neville Smith of Speedwell came into M Shed with a corked glass jar, which he said had been found in a cavity beneath the doorway of “the yellow brick church” on Greenbank Road in Easton. It was discovered during building work to convert the church into a mosque. The church he was referring to was once known as Castle Green Church, known locally as the ‘Lego’ church. It now operates as Easton’s Islami Darasagh.

Around a year ago, Neville Smith of Speedwell came into M Shed with a corked glass jar, which he said had been found in a cavity beneath the doorway of “the yellow brick church” on Greenbank Road in Easton. It was discovered during building work to convert the church into a mosque. The church he was referring to was once known as Castle Green Church, known locally as the ‘Lego’ church. It now operates as Easton’s Islami Darasagh.

Inside the jar were a number of well-preserved artefacts: a newspaper dated 1901, five Victorian coins dated 1900-01 and two Edwardian stamps (likely to date from 1901) attached to a blank sheet of paper with a barely visible watermark containing an image of the Royal coat-of-arms. The watermark was of great interest to the donor who imagined that the gothic font and the Royal Arms were indicative of a mysterious coded message. “It looks like Elvish to me!” he joked. However, on further inspection, it was clear that the watermarked words were “Charter Vellum”, a widely used watermark of the time.

This unexpected discovery is a builder’s time capsule, commemorating the time that the church was built. Finds like this are not exceptionally rare, but exciting all the same – particularly for the discoverer who has had the thrill of unearthing hidden treasure.

Rhian Rowson, Curator – Natural Sciences

We provide an identification service, and during a Bumblebee identification workshop I ran (for information on our workshops you can contact us) one of the attendees presented me with a cluster of tiny pots made out of mud. They were found inside a PVC frame of double-glazed front windows in a house in Bristol, when the owner was having their windows replaced.

We provide an identification service, and during a Bumblebee identification workshop I ran (for information on our workshops you can contact us) one of the attendees presented me with a cluster of tiny pots made out of mud. They were found inside a PVC frame of double-glazed front windows in a house in Bristol, when the owner was having their windows replaced.

I recognised them as being built by a solitary wasp. Solitary bees and wasps (which have no queen but build their own nests, filling them with food for their vulnerable young) are a particular passion of mine. There are just under 600 species in Britain, of which about half are wasps. This one was a spider hunting wasp, of which there are 13 in Britain. For those afraid of house spiders I have bad news, there is no spider hunting wasp in Britain

that feeds on these leggy giants! They generally hunt smaller ones.

Spider hunting wasps tend to look more like parasitic wasps (not like our common social wasps, which are much bulkier with black and yellow stripes) and their movement is very jagged and jerky. In Britain there is only one species that produces little mud pots to store food for its young. This species is called Auplopus carbonarius.

Amber Druce, Curator – World Cultures

One of the things that inspires me is all the seemingly boring things in museum storage! Sometimes they’re the pieces that delight our researchers the most and it’s amazing that someone recognised their potential importance and knew to keep them.

We’ve had whole papers written about little fragments.

The Bristol Mummy Project (1981) took samples from an unwrapped mummified Egyptian man and absolutely everything was deemed important. Even these tiny seed samples have been analysed, radio carbon dated, published and discussed at conferences!

These lotus flower fragments were excavated from an Egyptian tomb in 1909. They were donated to Bristol Museum as part of a burial group but excavation reports suggest they’re associated with a group donated to Manchester Museum. We’re hoping to reunite them soon.

Without background information, out of context, it would be hard to justify keeping these strange looking objects but because of the stories they reveal, they’re invaluable to us.

Kate Iles, Curator – Archaeology

In 1825 William Augustus Miles excavated a Bronze Age burial mound known as the Deverel Barrow. He found the cremated remains of 30 people and 21 pottery urns.

This is one of those urns. It was given to the forerunner of the Museum in 1826 making it one of the first objects ever collected. Made around 3500-3100 years ago, it is also one the oldest, largest and most complete pots in the British Archaeology Collections.

It inspires me every time I look at it. I think of the people that built the barrow and wonder who was buried with this urn. I also think of the antiquarians that excavated and donated it and started Bristol’s amazing archaeological collections.

Lisa Graves, Curator – World Cultures

Whenever I see this painting in the Curiosity Gallery at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery it inspires me to look at the world in a different way. The way Aboriginal Australians view the world is captured in their art. The way they see their lives bound up in their land and the mythical ancestors that created it reminds me that there is never a single viewpoint. The colours and the bark itself make me feel warm, with the sun on my skin, as if I’m standing in the red earth of North western Australia.